Margaret Begbie

National Fire Service

Tadeusz Brylak

Polish Army

James Drysdale,

Gunner, Royal Artillery

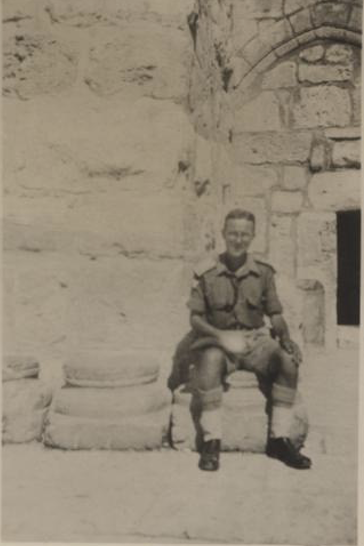

The Reverend Joe Ritchie, Army Chaplain, 1907-1996

Rev. Joe Ritchie as a young man.

Background

I first met the Reverend Joe Ritchie, a native of Dunfermline, in the mid 1970s when he was a minister at the West Church in Haddington, East Lothian. At that time, I was completely unaware of his eventful time as an army Padre during the Second World War or, naturally, of his very narrow escape from the sinking of the Lancastria. What follows is a significant section of Joe's autobiography, compiled by himself, his wife Frances, and his family and quoted at length thanks to the permission of his daughter, Madeline. I am very grateful to her for this privilege.

Joe's wartime autobiography paints a very detailed picture of both the range of duties and experiences and the dangers of a war-time Padre's work but also lets us look into the daily lives and experiences of Padres at this demanding period in their lives. It's frankly difficult to imagine that anyone will be ever again be in a position to experience the range of places, people and events that Padre Joe Ritchie experienced during his war service. This is a priceless account of a Scot in the British Army during World War Two and I hope you will forgive me for quoting it at length. It's worth the read!

He begins with his call-up and his time in Nantes before having to evacuate in the face of the advancing German forces.

"Declaration of War - September, 1939

My role as Army Chaplain began when there came a call for young ministers to volunteer for military service in the event of war with Germany. For the past few years we had heard Adolf Hitler on our radio rousing the German youth to assert themselves in the world as a kind of super race; they were no longer to tolerate so inferior a status under the Versailles Treaty. All Europe was agog. Confident that war would be averted, our army was unprepared, our navy depleted and our air force very small; very few people believed that war would be declared.

Then on the 3rd September, 1939, Germany invaded Poland and Britain was forced to declare war. The very next day was a Sunday and during morning service the air raid siren sounded. A sudden fear descended on everyone as though it was the crack of doom. None of us ever forgot it.

Call Up Papers

My call up papers arrived immediately, I had never dreamed of such a turn of events. I reported to the great gathering in a tented camp in Crookham, Berkshire. I had to go to London to be fitted out with an officer’s uniform including a Sam Browne belt, Doo-lichter hat and three pips for a Captain’s grade. The familiar battle dress came later, something which I was to wear for five years. There was no instruction given. I was a commissioned officer in the Royal Army Chaplains Department (R.A.Ch.D.).

No instruction or training at all was given to Chaplains, save for one brief meeting with a retiring Chaplain General. All I can remember of his address was: “If you can only see sin in the bottom of the wine glass, you will be no use as a Chaplain”. It was interesting enough getting used to uniform and living or being billeted in big houses, though for the most part we were in camp. I was able to organise services in a very general way for Sundays, but it was all a bit chaotic. Then one day the Chaplains of that camp were called together and were told to prepare to cross the Channel for an unknown destination.

Departure for France

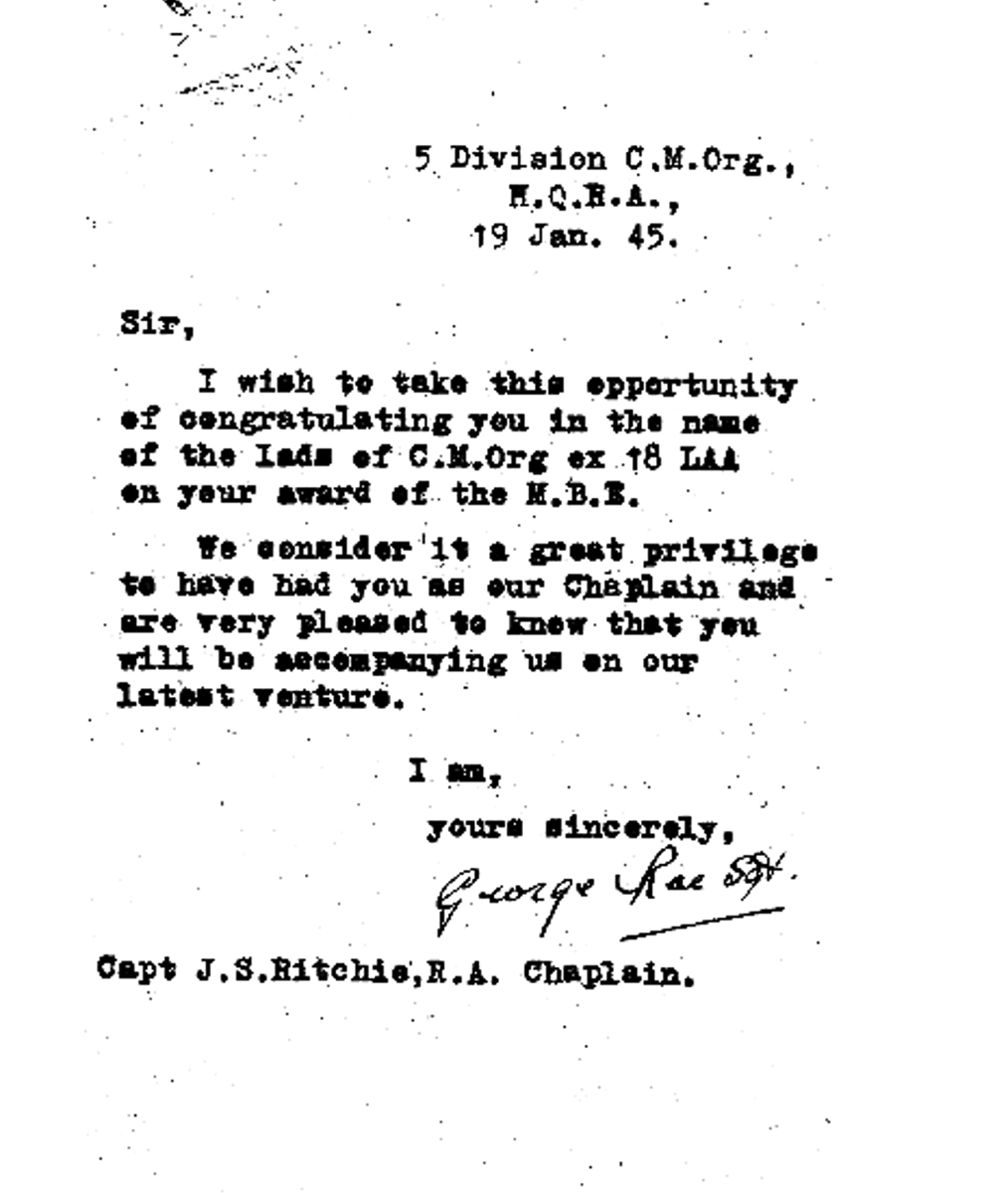

In the event, I was appointed to a base area on the western seaboard of France. I travelled by train across unknown French territory by night and day. The carriage was well filled and included one young Roman Catholic priest. He amused us all by swearing at the French people and their ways, quite an unusual fellow but I never saw him again. Eventually I landed at Nantes, a great industrial city on the banks of the Loire, where I was billeted in a typical French terraced dwelling with a Colonel who had an Italian name. There were three other officers and it was all very intimate. I was given a 15cwt. truck and a Scots driver. I had to serve the city and the surrounding area and find out where the Scottish regiments were. The Scots boys and the non-conformists, to distinguish other denominations from Church of England and Roman Catholic, were billeted all over the city and surrounding country.

I loved to go up country to visit the barns and all over the French countryside. It was very late autumn, apples hung heavily on the trees and there was a lot of morning mist and sunshine. In the city itself the men were housed in great factories. I remember particularly the 'fabrique' for the Petit Beurre biscuit where the only form of heating was open brazier stoves. That winter was the most severe I have ever known; in that same factory when men would comb their hair, with a little water, the water virtually froze on their heads, and breath came out like white vapour. We all learned to line our trousers with brown paper. The River Loire, so great an expanse of water, was frozen completely across.

Monsieur et Madame Avril

In my first survey of the city I went to the highest point to survey it all and to study my map when a Frenchman asked if he could help in any way. I told him I wanted to learn my way about the city. “I can help you sir” he said, “for I am a postman”. This was a first meeting of many with Monsieur Avril. I was familiar in his home, a little white washed cottage; his wife, a Breton woman, was most hospitable and I loved paying a weekly visit to that home and family. Monsieur Avril had lost an eye as a very young soldier in the First World War and had a glass eye which leered towards me as he spoke. There were two teenage boys in the family, Jean and Xavier. Everything was so neat and tidy. The wine barrel stood at the foot of the little patio in the garden and there the rabbits were kept and fattened up for eating later. Madame was soft spoken and gentle though she used to rage at Xavier who loved to drink the wine. He was particularly amusing when I did not pick up what he was saying; he would repeat it slowly and loudly and if it had not sunk in, he spoke more and more loudly, much to my amusement.

Madame used to confide in me in front of her husband that she had wanted a big family with girls, but her husband would not have it. There was a simple radio to which we listened in to the fulminations of the Fuhrer. Madame would hold up her hands in horror and cry “Quel bete. Comme il est brutale”. The evening always finished with a hot cup of coffee, newly brewed, and some simple French bread. Sometimes over the radio would come gentle music with an easy rhythm. Madame would get up and take my hand and lead me in a simple dance to the admiration of all the family. She spoke in a Breton dialect that was very close to Welsh and Gaelic and showed me her Breton poetry. I remember I brought home a little pottery basket, painted and decorated from Quimpere, a famous manufacturing town. The Avril household was a touch of home which I much appreciated in this strange environment.

Joining forces with the Roman Catholic Padre

One day there arrived in our billet a young R.C. monk, Tom Hooper. “Good heavens” cried the Colonel, “we shall have open warfare between the Roman and Protestant churches”. The monk was from Buckfast Abbey, sent to be a Padre and had special dispensation from fasting and discipline, in order to fit in with army ways. He had no truck and was set to serve the same area as I was covering, so I invited him to join forces with me. We used to meet other colonels who were very amused when we introduced ourselves together. (These were the days before ecumenism broke loose upon us.) We both faced the same difficulties gathering our members and he used to say “Oh for a little bomb, then they would be pouring into our services with the fear of death in them”.

We got to know one another very well. He was always amazed when I would go to the NAAFI to buy bread for communion. Once we thought to look for other digs in that great city, but we gave up the struggle. One landlady showed us an untidy bedroom and said “Yes, you can have this if you don’t mind the two beds being used during the day”, and to this the Padre said to me in English “Brother, you’ve made your bed, you can lie in it”. Back in our own billet, we had a big fellow as a cook. He chased the young mistress of the house, but she would have nothing to do with him. At night he would return the worse for drink and when we would hear his noisy return the Colonel would laugh “That’s him, falling up the stairs to his bed”.

Sometimes the Scotsmen, just to be different, would demand a Scots Presbyterian Padre, and would not have the Anglican. One such group demanded my presence but I could only arrange to go on a Sunday afternoon. When I arrived there was no congregation present, the men were all sound asleep. The Sergeant said to me “I’ll soon have your congregation, sir”. His call to worship was not with sweet church bells, but with the loudest cursing and swearing. He told his men where they were bound for and it was into the barn for the Scots Padre whose attention they had demanded!

La Mission McColl

It was during these autumn and winter months I had found and made use of La Mission McColl. This was a religious settlement with a strong anti-drink emphasis. It comprised a little compound made up of the pastor’s dwelling house, a delightful little church, surrounding accommodation for lodging, a canteen and games room. In the compound outdoor games could be played and it was lovely when the trees came into spring blossom with a very pleasant perfume. This we used as a centre for soldiers gathering in their free time. I came to know the pastor and his wife, a friendly and gentle couple who took me to their hearts.

Because Paris had been overrun by the enemy, the Pastor and his wife were joined by Monsieur et Madame Ferret who came from the McColl HQ as refugees, a delightful couple. They assisted in the running of the canteen and were very anxious to have ladies from the Church of Scotland to help, and so arrived, two Scotswomen, who became known as “Les Dames Ecossaises”. These ladies, one elderly and one young, were dressed in blue uniform with caps, most becoming. The French women had expected Scots peasants who would scrub and wash the floors, and because it was not so they used to chide me, “Mais les dames ecossaises ne font rien”. Miss Rattray, the elder, was a strong character, widely travelled and typically west end of Edinburgh. Margaret, the younger one, who was her niece, was very pretty, quiet, genteel and quite inexperienced.

Every Sunday night the troops used to gather and fill the little chapel to capacity. Amongst them I found good organists and most helpful Christians, Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists, Church of Scotland and Anglicans. The praise was something to be heard.

As the months moved on more and more refugees crowded into Nantes; our compound accommodation was used to the full and the French refugees also came to evening service; all standing forlornly at the very back in a little crowd. I would address them at the end in French. I hoped to comfort them for they were all very bewildered and fearful of the Germans.

Amongst the McColl Mission Parisiennes there was a young girl called Giselle, a very pleasant, well educated young lady. She practised her English on me and I quite enjoyed her company in a quiet way. She used to accompany me to my digs where I lived on my own with a delightful French couple, Monsieur et Madame Amy, who lived in la Rue de la Fraternite.

Monsieur et Madame Amy were committed Christians and members of a charismatic faith healing group. In my early days I felt they were testing me out when they would invite me to evening prayer on a Sunday night down in their own living room. From there our prayers would ascend as each knelt at our own chair beseeching God aloud and with much movement and agitation of chairs. Evidently I passed muster and our relationship became very warm and natural. They were great fun. They had no children, a great disappointment to them, but they were very kindly. They grew to be close friends of Giselle as well. The upshot of all this was, and much to the consternation of Madame Ferret, Giselle flitted into the room next to mine for digs."

Joe Ritchie on the left, Monsieur Amy in the middle and Joe's driver on the right in Nantes.

"Affairs of the Heart

In our free time at the weekends the whole household used to go cycling, carrying our sandwiches and picnic. One winter’s night, aided and abetted by Madame Amy I am sure, Giselle invited me into her room and there she confessed her love for me. It was a very emotional experience, for Giselle was very much in earnest and a good Christian lass. I had to explain to her as gently as I could that, in my present situation, involved with the army at war; I was not free in any way to hear this unexpected avowal. I had the highest regard for her and hoped she understood my wartime circumstances. Unhappily Madame Ferret had, with a woman’s intuition, guessed the way things were with Giselle, and was very hard on her. Madame Ferret had her own daughters in Paris, about whom she worried tremendously, and I had to pray with her for their safety and well being.

During this time I had to deal with some very delicate situations. A delightful young English soldier came to ask my counsel. He was married, but here in France, he had met a young girl whose husband was away on military service. Loneliness had thrown them together and he wanted to know if it would be right for them to be temporarily husband and wife as they had grown very fond of one another. I counselled him as gently and as strongly as I could, that neither of them should get involved in this way for their future happiness. They were obviously young people with a conscience, very earnest and lovable and I hope I helped them.

Chance Meeting

It was here in Nantes one afternoon, as I was walking in the busy shopping area, I passed a young soldier who seemed somehow familiar. A few steps on we each turned and looked back, and to our great surprise, knew each other. For this was Forest Syme, my brother Duncan’s wife’s youngest brother. We met for a meal on several occasions after that in a little bistro, but later on our ways parted.

Financial Matters

The English Padre who was responsible, along with a French committee, for the big central canteen, run by the local people, asked me to take over while he went on leave. I wondered why he did not ask some of his Anglican Padres, but I undertook the job which involved gathering the cash at nights and banking it the next day. There was a turnover of thousands of francs and I had to visit the bank regularly. The wet weather had suddenly worsened, rain and wind, so I decided one evening to go to the bank later. For safety I stuffed many thousand of francs into my Wellingtons and forgot all about them. When the English Padre returned all was normal. About two months afterwards I had occasion to wear my Wellingtons again and to my horror discovered them stuffed with thousands of French francs. I took them to the bank and wrote the English Padre who, had meanwhile, been transferred to another area. He wrote back with great amusement, saying that the committee had wondered at the sudden drop in income! The English Padre came through and saw the committee and the matter was resolved happily."

Joe's story continues now with his first contacts with the German army.

German Advance from Paris

"So life continued here and meanwhile the news got worse and worse; the Germans were advancing rapidly from Paris but we had still to hold the fort as a base area. Suddenly there was a great exodus of personnel and out on the highway a truck drew up containing ‘Les Dames Ecossaises’, Margaret and her aunt. Miss Rattray looked at me with tears and said, “Are you not coming?” and I said, “No, I am under orders to stay.” They had heard the worst of the news about the German advance and were fearful for my safety. That was the last I saw of them. I went down to the great NAAFI stores where men were clearing out leaving their goods behind in their haste to leave. I asked if they could give me these two great slabs of sultana cake and a box of Kit Kats, which were quite new to me. Madame Amy was very fond of the cake and the Kit Kats and because every Sunday morning they invited me down to breakfast this was a little return I was able to make.

A day or two passed, strangely quiet, and the French people asked if we were going to leave them to the enemy. It was a sad and delicate situation for us all. Then word came that I must leave immediately, meaning that my waiting behind had been for nothing. My driver brought the truck and we sped away along the highway, making the forty miles to St Nazaire in no time. The sky was full of enemy planes as they strafed the road which was now heavy with fleeing vehicles. Again and again we had to stop and throw ourselves into the ditches for safety; it was a long and frightening journey. When we did reach the port of St Nazaire there was nothing but a great plume of heavy, black smoke caused by the great petrol tanks being destroyed along with all of our transport; my truck was also taken and destroyed.

All that night we lay on the pier under the open sky, but never slept for it was very cold. The day broke and the hours passed slowly. We saw a little boat arriving and it took us on board and ferried us some miles out into the Bay of Biscay where the great liner, Lancastria, lay at anchor. On this great ship all the strays and stragglers from the allied retreat had been assembled; we must have been the last departing ship from France and so we were glad to set sail."

The sinking of the Lancastria

RMT Lancastria, sunk off St Nazire on the 17th June, 1940 with the loss of up to 7,000 lives.

[Thanks to Wikipedia]

The sinking of the Lancastria

The Cunard liner, Lancastria, built on the Clyde and launched in 1920, was normally used to carrying passengers across the Atlantic or on cruises around the Mediterranean. It had been requisitioned at the start of the war for use as a troopship ferrying troops from Canada to the UK. It was then used to take troops to Iceland during the British occupation of the island and to evacuate troops from Norway after the German invasion of that country. Two weeks after Dunkirk and the evacuation of the British and Allied forces from northern France and Belgium, the Lancastria was sent to evacuate troops from central France and arrived off St Nazaire as part of Operation Aerial. There she took on board between 5,500 and 7,200 troops, airmen, diplomats and civilians, ferried out by smaller craft. No one has a verifiable number, thanks to the confusion of the time but, obviously, what ever the final figure was, it was well over the normal complement of around 2,200 passengers.

On the 17th June the ship was bombed by JU-88s and three, perhaps four, bombs hit the ship, leading to its sinking within twenty minutes. The loss of life was horrendous and this sinking can lay some claim to having been the worst ever British loss of life at sea. Joe Ritchie was a very lucky man indeed to have escaped from the sinking ship and he now describes his experiences during this event, a disaster so serious that Churchill forbade newspapers and the rest of the media from announcing it. The British public only got to learn of the loss of the Lancastria some five weeks after the event.

The overturned hull of the Lancastria with men both on the hull and in the water.

It's quite possible that one of these figures was Joe Ritchie.

"Bombing of the Lancastria

I had gone to a cabin on the upper deck and, dressed only in my vest and pants, I lay down on a bunk because I was very tired. Suddenly I awoke with an ear splitting crash, then another and another. It was the enemy planes scoring direct hits on our almost ‘sitting target’. I scrambled out of my bunk grabbing my helmet but leaving my clothes behind. I rushed along the passage expecting the great door to have been sealed but the bombs had ripped it open. By this time the boat was at a terrific angle and I had difficulty moving, so half walking and half crawling, I passed the steep galleys that led down to the lower decks and saw that the steep steps down were crowded with a vast sea of faces all trying to escape. Men were so tightly packed that it was not possible for them to move up or down; I can never forget that terrible sight of doomed men, knowing that there was no escape for them.

Escape into the sea

I remember seeing a Salvation Army Padre whom I knew slightly; his face was white and I reckoned he did not know how to swim. The whole atmosphere was yellow with smoke and acid fumes. Our own anti aircraft guns were shooting furiously at the enemy planes and I could see blood on the faces of those who manned the guns. By this time the angle of the ship was acute and I was now on my hands and knees crawling upwards as far as I could. Suddenly I caught sight of swinging davits that had once held a lifeboat. I decided my only chance was to swing out at the end of one and drop into the sea. I slipped off my boots and stood in my vest and pants still wearing my helmet but I had not reckoned on the davits being so high above the water. I swung out and dropped and dropped and dropped, then sank and sank and sank till I felt my helmet almost lifting off my head, but still held in place by my chin strap. I struggled to the surface, spitting oil and water. Breaking the surface I took one glance at the sinking ship before I swam directly away, not wanting to be sucked down should it submerge.

After swimming for a long time I turned on my back and could see the keel of the Lancastria; all along that exposed part of the keel men were clinging on for dear life. Strange though it may sound, I heard voices singing, as though in defiance. “Roll out the barrel”. It was obvious that these men could not swim. In a moment the great ship was submerged. The most frightening part now occurred when the enemy planes swooped low over the water. Planes slanted sideways and I could see the pilots and crews as they fired at those who struggled to save themselves. The fire burned holes in the water and I heard the hissing ping as bullets struck the sea. Then the Germans were off, having accomplished their task. By this time I had grasped a small piece of wreckage which helped keep me afloat. Shortly after I heard the cry of a young soldier who shouted over to ask if I could help him; we shared the tiny piece of wood and it gave us rest until a raft loaded with men arrived with room for only one. I told the young lad to take the place. Then the waves parted us and I was once more alone, swimming breast stroke and back stroke. All the time I was alone my thoughts had been with my grandmother and I was strangely calm. I was very young when Grandmother died and never had a chance of knowing her as a grown boy. But oddly enough she was the only one of my family in my mind as I drifted hither and thither.

Rescue by French Fishermen

Suddenly I was aware of another ship’s raft coming near. I asked if there was any room but they could only let me hold on with one hand. But this was something at least until there hove into view, a little vessel with civilian seamen. It was a French fishing vessel. Slowly and painfully we were dragged from our raft out of the water. With the support of the water, our strength had been sufficient, now however, deprived of that support, we were too exhausted to help ourselves. The French fishermen sat us on the small deck with our backs against the warm plates of the engine room. I sometimes think it was not a fishing vessel as it was so black and oily.

Transfer to English Merchant Ship

And so we sailed away, strangely careless of what had happened. Our time in the water had seemed endless; we could not rightly judge the length of time, yet by a mercy, the Bay of Biscay was reasonably quiet and on we sailed, hopefully towards the English coast. Out of the blue there appeared, first the mast, then the bulkhead of what transpired was an English merchant ship. We sailed close in and we were soon all lifted to an upper deck. There the most frightening experience of all began. We were put down in the very bowels of the ship with the hatches battened down over us; there we lay in the dark, in an ice cold atmosphere, huddled together, lying between the wooden boards, knowing that there would be no escape should there be any further enemy fire.

We heard the Captain had spread a great Red Cross flag on the deck of the ship and no soldier must be then visible as our safety depended on it. So we sailed away out into the Atlantic and headed straight back for the Channel and Plymouth. All during that wretched time we knew if enemy bombs hit us we would be like rats in a trap, unable to escape. Into our darkness was lowered a great vat where we could relieve ourselves and make our water. Eventually, after what seemed an age we were allowed up on deck; the darkness was falling and we had arrived at Plymouth Hoe.

Landing in Plymouth

We stepped ashore on the quay, barefoot and half naked and were each handed a blanket. The WRVS were there, offering help, but we were all whisked away in army transport up to Plymouth Barracks where we were examined by the medical staff and put to bed. In the morning we were given a wonderful breakfast, then sent down to the Quartermaster’s store and fitted out with battledress, new army boots and puttees. Being fit we were commanded to return to our homes where further orders would be given to us.

Arrest in London

I made it up from Plymouth to London with little problems, but there were hours to wait for my train to Scotland. Not being familiar with London, I tramped around the central area, beguiling time as best I could. Unknown to me, I had been observed by two Canadian Military Police, for I had often been retracing my steps in order not to get lost. I then found myself hedged in by these two MPs with one on either side as they demanded to know who I was. Of course my story aroused all their suspicions. I could understand their concern as I was wearing no badges of rank, I had no identity card and I was wearing entirely new clothes. I suggested they phone the War Office. They crowded me into a telephone kiosk, but got no satisfaction from the War Office. I was hustled out, firmly gripped, as they suspected that I was a spy. The Canadian MPs hailed the Metropolitan Police, who then hailed an open taxi and, in the midst of London Bobbies, with a great crowd of onlookers, I was taken to Scotland Yard. There I was questioned up hill and down dale, no one believed me and the story I had to tell. Following imprisonment under special guard, I asked that phone calls be made to the War Office and the Royal Army Chaplains Department. Eventually, after a long, long time the confirmation came through and I was informed that I was free to go. I bent my head and wept silently with relief, while the police officers turned their heads away to give me some privacy.

Freedom at Last

I was released, given a cup of tea and sent by taxi for the last train which arrived in Edinburgh about four in the morning. It was noon before I arrived home in Dunfermline; I opened the door and Mother saw me. She turned so pale; then, when she knew me she wept and embraced me. The night before, Winston Churchill had spoken to the nation and explained that, now Dunkirk was ended, all others must be deemed lost. The news of the Lancastria was never revealed until many years after. We had, as a nation, suffered such reverses at that particular time; Churchill did not dare tell folk of the loss of the Lancastria, a great liner which had been sunk by enemy fire with the loss of well over three thousand souls."

The international meanders of a war-time Padre

It was wartime and Padres were no different from soldiers in that they weren't given much time to recover from their experiences and to relax. Joe Ritchie was soon on his travels again.

"Joining the Cameronians August 1940

So I settled down in the uncertain climate of an enforced leave, but was soon called again [this time] to join the 2nd Cameronians (2nd Battalion Cameronians – Scottish Rifles or Scottish Greybreeks). This was a Scottish regiment raised in the old covenanting days by the covenanter Richard Cameron who yielded his life for Christ’s cause and crown at the hands of the Redcoats – the King’s Men. I was welcomed by the Colonel and officers to their camp near Elgin. Meanwhile, Hitler described the British BEF evacuation from France as ‘a lion licking her wounds’. We were soon dispatched to our new camp, to a little estate called Strowan House, near Comrie, Perthshire. The officers occupied the estate house and the men were under canvas. It was a great experience getting to know foot soldiers as they were a very good lot of men and officers.

The Colonel was a delightful Englishman, he and I came to know and like each other. By this time I was getting accustomed to the army language which was neither gentle nor courteous. Here in Comrie, we were in training again, and many a day we had tramping over the surrounding hills. One platoon officer made us walk through the burns so that the water moulded the leather of our new boots into the shape of our feet. Our puttees were a great help, binding the top of our boots to the bottom of our trousers which made walking so much easier.

Lighter Pursuits

Near our camp was a little schoolhouse. The school ma’am ran a canteen for the soldiers, and other locals came to help. Amongst them was Mrs Goldberg, from a very well to do landed gentry family. Her daughter was a lovely singer and now and again she would come down at night and I would accompany her on the piano. Everybody was delighted with her singing. I was invited to the Goldberg’s home, a place of solid comfort and great gardens. When we were called to move camp, she gave me £25, which was a great sum in those days. This was for the comfort of the troops in my charge; the Colonel was very pleased with the gift.

Liverpool Blitz

Now the scene changed and we were transported from lovely Perthshire hills right into the midst of the Liverpool Blitz. We were billeted in new houses on Huyton Estate. Every night we were called out on duty. It was a wonderful and fearful sight to see the dockyards and the down-town area brilliantly lit by enemy flares in the dark night sky and the great noise of tumbling buildings and sprouting fires. Sometimes there was entertainment for the young officers and one young Edinburgh Subaltern fell in love with the Anglican priest’s daughter. Her father came to see me; anxious about his daughter’s ‘friend’ and wanting to be assured he was the right type of young fellow. I was able to reassure him and eventually they married, but by that time we were sent far away.

Ireland September 1941

First we were sent to Ireland where we stayed through autumn into winter and got to know the Irish folks very well. The Cameronians were stationed at Lislooney and Killilea with our nearest town being Armagh. Here we lived in Nissen huts; I had one all to myself so I painted it inside a fierce sunshine glow, gathered all kinds of magazines and papers and set tables for the men to write their letters. It was here I had my boots stolen. I put up a notice asking for the return of my boots. The whole camp was indignant at the theft, and so the Quartermaster issued me with a new pair. My Batman was Johnnie Musher, a little, five foot Glasgow ‘keelie’ who was married to Mag, ‘the wife’ and had an adopted son called ‘The Boy’. Johnnie was a very decent, wee man but he grew stout and puffy and had to eventually be retired out of the army.

I was then given Davie as my new Batman and driver of my 15cwt truck. Those were very happy days; out on exercise both day and night. Brambles were in season and so platoons were sent in turn, to gather the fruit; we had brambles for months, in everything! It was terrible!

Lislooney Church

We got to know the people and I commandeered Lislooney Church for Sunday services along with the little hall run as a canteen by the ladies; it was here that I ran a mission. I was advised about a well known evangelist, so I invited him to spend a week with us. He filled the hall every night, in spite of his rather curious way of speaking when he would keep the sound and fury of one sentence going right into the next until our hearing and understanding were a little shattered to say the least!

The local minister was Rev. Tom McKinney and along with his wife, Tillie, were a delightful pair. Each Friday I went along to the Manse for my weekly bath and to have supper with them. Tom played tennis and was a great humorist; what fun we had. I got to know all his members and appreciated this opportunity to get to know the Irish in this way. There were fox hunting gentlewomen who lived in a great house and farmers whose hospitality was something to experience; many of the folk we met had kissed the Blarney Stone for sure!

In Ulster, everything at night was done according to the phases of the moon. On a really dark night you could not see a thing so meetings had to be arranged by the moon, so to speak. I enjoyed my time in Ulster very much and still have the warmest memories of that land. It was during my stay that I got to know the surrounding countryside and many of the Presbyterian ministers."

Service overseas

Padre Joe Ritchie with fellow officers.

Location unknown but probably Germany.

Voyage to Durban March 1942

"However we were still under arms and once again the call came, “Prepare to move!” This time it was far beyond the seas; we sailed the Atlantic and round the Cape of Good Hope, seeing Table Mountain to advantage on a lovely morning. We then headed north to Natal with our destination being Durban. The voyage was of great interest as we watched flying fish, porpoises, dolphins and all the wonders of the deep. Night and its complete darkness was always a trial for us (no blink of light was allowed); we would drop depth charges now and again in case of submarines following in our wake.

On Sundays we would hold services on deck and at night, in the hottest atmosphere below deck with all the curtains drawn, we were stifling. It was here that I got to know all the officers and men as we were at sea for weeks. Durban was a fine city to visit and I had a trip through the Valley of a Thousand Hills, the country of the Zulus. The winding mountain roads, the vast vistas and the open sky with the cactus flowers made a memorable impression on me.

Madagascar July 1942

From Durban we set sail for Madagascar, a French occupied colony which was threatened by a Russian / German invasion. Prior to this there had been little warfare there and so we had to go ashore by moonlight in landing craft and lie low until the moon came up and we were able to move along sand laden paths, weary with the great, heavy packs on our backs. When dawn broke we encountered many dead Madagashi in a field; the stench was awful, the unburied bodies were swollen in the heat and what sorry spectacles they were.

Our stay here was not long, I travelled the country on foot as far as Tananarive and on one occasion sat down to rest at a village and was then invited to eat with the natives. The women folk went to bring fresh bananas which were kept in long pits, like potatoes back at home. The fruit was green and unripe but the women peeled the bananas, mashed them in native flour then fried them in oil. They were very pleasant to eat. All around the village grew a low, bush like growth – ground nuts. One of the locals pulled up the green foliage (like a carrot leaf) and there, on the roots, hung a great cluster of monkey nuts; invaluable for food, oil and all kinds of things. Everyone spoke French so we could get along quite well and, of course, they were all Catholic.

India

From here we sailed the Indian Ocean and landed at Bombay, whereupon we travelled by train to Ahmednagar; the journey was very hot and tiresome and our whole stay in India was very wearing upon the mind and flesh. Each Sunday I held services in a hutted encampment and it was good to have such crowds. It was here that I made a fatal mistake. Traditionally, when the Colonel could not attend a service to read the lesson, he would appoint someone else to take his place. On one occasion he appointed an Officer who had been very blasphemous, deriding the Christian life and ostentatiously promoting the way of the world. The Colonel was unaware of the officer’s views, however I was deeply concerned about this, “How could I let this man read the Scriptures during the service?”

During the service I decided on the spur of the moment to read both the Old and New Testament lessons together myself; this put the cat among the pigeons. The Officer concerned was so angry he came to my tent and wanted to fight me; I was utterly exhausted and said, “What’s the use? You’re far stronger than me.” The Officer swore he would get even with me and went around telling all the officers how I had insulted the Colonel. Eventually the Colonel called me to his hut and explained that, as his appointee, I should have accepted the Officer. I apologised, never having had any intent to be discourteous; the Colonel was a good man and he and I got on well.

Joining the 18th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

Soon after this an Anglican Padre, high up in the ranks came to see me to ask if I would like a transfer. I was surprised by this as I’d only ever wanted to be with the Cameronians. The Padre went away and the next thing I knew I was being transferred; I was angry and heart broken as I had got to know and love the men I served. I wrote to the Headquarters accusing the ‘Red Hat’ of a lack of frankness and discourtesy; indeed there was much dismay at my leaving among officers and men. The Colonel felt guilty too, I believe.

Learning Urdu

In the months that followed I was often alongside the Cameronians on our tours of duty and was always given the warmest welcome by the Colonel and the men; I had loved being with them.

However, I was transferred to the Indian Army where a Scots Colonel of the old school had demanded a Padre of his own; the Colonel was a kindly man but more interested in having a Scots Padre than doing anything effective to help. I got an Indian soldier from the ranks to be my Batman and he immediately put up three stripes and assumed the rank of Sergeant; he was a funny lad! One of the other Indian soldiers offered to teach me Urdu; we met on different occasions but my total conversation in Urdu resulted in, “The cow is a sacred animal”! My tent was alongside a tent of Indian soldiers and each night one would begin telling a story and from then there would be continuous and infantile laughter. When I asked about this tiresome behaviour an Officer told me that the Indians recite stories continuously and laugh uproariously at the simplest of things. It was pretty nerve-racking for me.

India to Iran August 1942

We journeyed to Basra in Iraq then on to Iran where, mercifully, I was attached to a Scots regiment, the 18th Light Anti Aircraft. The men were mostly from Glasgow and it was here that I met Tom Brown whom I was to come to know and love. We encamped at Kermanshah and Qua’s-i-sirin, a wild and lonely country area. While I was here I was invited by a local chief to a feast; the chief ruled over a great territory with many shepherds and sheep. The village was an ancient place of mud brick and stone buildings, little crooked byways and water running in guided rivulets everywhere. The ‘Papalce’ was just a greater house with open doorways for windows where the sun streamed through and where we sat on cushions and were offered tiny brass cups of sweet coffee. There was no actual sugar but we were given a local sweet to put in our mouths then we drank the coffee through the sweet which had the same effect as sugar. At one point, as we approached the hamlet where the ‘King’ lived, two wolf hounds came leaping towards me; I was very frightened but, thankfully, they did not molest me.

Living in the Persian Caves

Persia was a wild country; the plains were rough pasture land and were very hot in the summer. Our men were stationed here and also far up in the mountains where the winter snows kept their white covering so I was required to visit them there in their little units. My driver / Batman, George, loaded the truck and we set off leaving the heat of the plains behind us. George, a Yorkshire man, was a good enough driver but not overly confident.

Travelling higher and higher by great winding roads we came, at last, to the snow level where the road led through many passes; every few miles would be a Gun Site with ten men stationed there. At one of these sites the men had made themselves very comfortable in a cave; they had a warm brazier lit for warmth and cooking, wild animal skins lined the walls and doorway and their make shift beds were very comfortable. The men treated me royally and when night came they said they had prepared quarters for Officers and took me along to another little cave with a bear skin over the entrance and sheep skins on the floor. I never slept a wink! Each moan of the wind sounded like some wild beast intruding for it was a very wild country. I was so glad to join the men for breakfast and have the comfort of fellowship. Each evening I had an evening prayer with them; Catholics, Protestants and unbelievers were all quite happy to sit in; old divisions mattered little so far from home in this snow wilderness.

Close Encounter with Wolves

It was on one of the Gun Sites that George and I had our first encounter with wolves! We were well on our way when we came to a Persian Police Post; this was a tall, mutty built, high roofed room where the policemen slept and had their meals. George and I settled in to share with them, when all of a sudden there was a great shout. All the policemen fled out with their long rifles. George and I followed and, there, we saw our first pack of wolves; the leader looked so fierce while the others followed in single file behind him. The wolves were quite close although a deep ravine separated us; the police, however, were taking no chances.

Going through the Kangavar Pass early one morning, we found the air cold and bitter as we topped a high bend on the winding road. The track then led steeply down so George changed to a lower gear; as soon as he had released the truck from engine power we began to slide. Nothing could stop us. We slid this way and that, then right over to the edge and gently over and over. We were beyond thought by now, we just held our breath. The valley swept precipitously downwards but our little truck righted it self and stuck fast on a path that led round the mountain.

George and I sat and looked at one another; we were beyond speech. When we ‘came to’ we gingerly let ourselves out and walked along the path until will reached the main highway; here we sat, not knowing what to do next. A long while after a great truck appeared with men whom I deemed to be Russian. They very quickly understood what had happened and in no time had unwound a great length of chain on a windlass. This, they attached to our truck, and then slowly, painfully we were winched out of the snow and mud until we were on solid road again. What a relief it was to be mobile again!

With grateful thanks we sped on our way till suddenly we crossed a number of holes in the road and came to a complete stop – all the suspension had gone. It must have happened during our fall but the ice and snow had held things in place; now with the sudden, rough shock of the pot holes the true extent of the damage was revealed. Luckily we were not far from one of the Gun Sites and so men came along to help tow us off the track. We were then given another truck on loan to enable us to continue our journey to Teheran.

At one post, Ecbatana, (a town associated with Jonah in the Old Testament) we met up with some Indian troops and were offered basic accommodation and a bath by some Persian peasants. I accepted gratefully. The bath house was just an old fashioned outhouse where a great cauldron was fired from sticks beneath and a peasant woman, veiled and dressed in voluminous black, filled up the bath. She stood by for me to get into the bath but I signed that she need not wait as I enjoyed a welcome bath.

My Colonel, at this time, was of Italian extraction; a very gentlemanly soul who always kept himself so clean and scented, quite unmilitary like, but he was a very kindly man. I was very fortunate as I had met some ogres of commanders whom I would have hated to be under. Because of belonging to the Royal Army Chaplain’s Department I had a sense of freedom; I was responsible to this Department and was only sent down to various battalions as courtesy."

Standing in the back row middle, Padre Joe Ritchie is shown during his service in Persia

"Iraq

Back down in the plains again, the 18th Light Anti Aircraft was assembled together and joined with the Y Division to move the trucks across Iraq en route to Baghdad. Our way led between the great rivers, Tigris and Euphrates, and it was very mountainous and barren with great stretches of desert. We camped at night as best we could and I remember setting up our tents near a dried up river bed only to wake and find that we were in a sea of water, following the rain during the night. It was quite frightening to find ourselves wading through mud where, only a few hours before it had been dry desert. At one station where we camped there was an immense face of solid rock and, in front of the rock, a great, deep, carved rock pool. The soldiers did their best to convince me that this was where Moses had struck the rock in the Old Testament story; it certainly looked like it! The carvings on the rock face recorded military movements from long centuries past; I think they are called the Bisitun Carvings.

Strange Sights

When we eventually reached Baghdad it was just another Arab town and we did not delay there long. All I can remember was seeing a man carrying a piano; he had a strap around the broad base of the piano and the strap was held by his forehead. I cannot imagine how he carried it but he obviously knew what he was doing.

We continued travelling for days, crossing the stony desert en route for Damascus. At one point, in the desert, the sandy track we were on had a lonely sign post, ‘To Babylon’. I often wish I could have stopped and gone to visit the excavated ruins there; later I was given a little hand book with photo prints showing ancient Babylon. Rising out of the desert stood the great pillars with carved animals, the entrance through the city wall. The pattern of streets was very clear, the broad way ran north and south and the parallel streets east and west. It was here that the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon had once been - one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

I always remember the nights when we set up camp and the great truck drivers would help gather stones for the fireplace. With hoarded wood and plenty of petrol, we soon had a hot meal ready which was most welcome as the nights could be very cold. Now and again on our travels we came across a Bedouin camp where the people lived under great black canvas tents – men, women, children and beasts. We had to search the barren hills for any grass and, at times, would come across the great, white skeleton of a camel which had died in its tracks.

Damascus March 1943

Eventually we reached Damascus and were camped high up in the hills between Syria and Lebanon. In the mountain range we found Jebel Mizar mentioned in one of the Psalms. We often found our way to Beirut then on to Damascus for we stayed a while in this area. Damascus was a very attractive city; the waterways interested me especially. There were the Twin Rivers, Abana and Pharpar and, from these rivers, the waters were led off in clear, blue rivulets to water the hillside terraced land. Half the delight of Damascus was that it stood right against the desert and all its sandy waste, but here was a city with water, lovely trees and cool places. Architecturally there was nothing much here although the ancient mosques were interesting. On the south side, the bazaar ran through the street called Straight where Paul, in the New Testament, came to visit Ananias to recover his sight. The house is now a little place of prayer for Christians.

Irish Presbyterian Mission

Two Irish ladies ran the Irish Presbyterian Mission in Damascus. As you entered the doorway in the mutty wall, a most unprepossessing entrance, you suddenly found an airy, octagonally shaped, paved area. In the centre of this was a round pool surrounded by a broad, low wall where you could sit and all above were the upper storeys with accommodation. Lovely vines and fig trees were trained up the walls and under the glass roof to provide shading in the heat of the sun. The troops were all made very welcome at the Mission and services were held regularly; as numbers increased the lady who ran the Mission just added more water to the soup thus ensuring there was enough to go round!

Damascus Bazaar

The Bazaar, itself, was very interesting and here we saw the silversmith at work with his Bunsen burner, tweezers and delicate silver wire making filigree brooches and necklaces. One old Arab cottoned on to me and invited me to see his wares; there he sat me down with a tiny cup of hot, black, very sweet coffee. The dark cavern in the shop was like an Aladdin’s cave with all its silks, furs and Persian rugs. The owner besought me to buy different things and when I tried to bring down the price his reply of, “Special for you, Soldier, only for you would I do this,” was delivered with a confiding smile. This story proved to be the origin of my famous children’s address ‘Special for you, Soldier’. Through Syrian friends I was invited to witness a Dervish dance; this was a Druse ceremony connected with their worship. Only men took part, one of whom was Master of Ceremonies. They danced around in orderly fashion one by one and bowed to the Master; young men who were dressed in blue and turbaned, were presented to the Master. It was all very interesting.

Lebanon Mountains

I took the opportunity to travel over the Lebanon Mountains and found, at the top, the great temple, a ruined memorial of the distant past. The heathen temple was called Baalvek and it was here that the source of the River Orontes could be found underground, sounding like a thundering tumult as it gushed down to eventually become a great river. In Baalvek we came across a delightful temple to Bacchus, the God of Wine; many pagan traditions were represented here. Some of the magnificent pillars still stood with their great plinth; lead penetrated the stones right to the top of the immense pillars to hold them in place but others had been destroyed by the Arabs who coveted the lead.

I also made a journey to Beirut; the descent to the Mediterranean was wonderful and as we approached the city, it seemed as if a lovely, blue cloud enveloped part of it. We discovered later that this was the Jacaranda trees in full bloom all over the city. I visited the University in Beirut where there was a great American influence. I also climbed Mount Carmel with thoughts of Elijah challenging the prophets of Baal and routing the pagan gods by power of the Lord God Jehovah.

Israel

Israel was a great experience; to visit the Holy Land was a fulfilment of an unexpected dream come true. The journey took us more or less from the snows of Mount Hermon right south by way of the Jordan waters to the Sea of Galilee, and from there down into the depths, far below sea level, to where the Jordan waters pour into the Dead Sea. It is a wonderful country whose surface land is full of history dating back to the time of Christ and, long before, to the Old Testament writers and the civilisations of Phoenician, Egyptian, Greek and Roman, reaching far into the past beyond the written word."

Joe Ritchie (on right) in Lebanon with some other officers.

Joe on the steps of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem in 1944.

Joe in Cairo, July 1944

Joe continued his description of his life in Israel:

"Much of the landscape remains unchanged from the earliest times, the Mediterranean, the rocky coast, the few harbours, the sandy desert soil encroaching further and further inland, yet marvellously restored by the Jewish nation; plantations and irrigation virtually winning from desert lands a well watered garden with its sweet scented orange groves, its vineyards, its olive groves and abundance of citrus fruits. Inland we came across a rough terrain of stony ground yielding brief harvests and, of course, the shepherd with his flocks of sheep and goats seeking out the water ways.

The City of Jerusalem

The hilly countryside soon broke up the landscape and the mountains rose until we reached Mount Zion on which Jerusalem stands today. The holy places associated with the life and times of Christ are so cluttered about with buildings, churches and merchandise that it is difficult to separate truth from fiction. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which embraces Golgotha where Christ was crucified, is almost impossible to imagine, as is the stable in Bethlehem where now stands a great Church edifice."

Joe then gave a long description of Jerusalem which is not relevant to our particular focus here. I take up his story later when he sailed for North Africa:

North Africa and General Montgomery

"When we left Israel our ship set sail for North Africa where the Eighth Army (The Desert Rats) was under General Montgomery’s command. We came by way of the Suez Canal and across into Egypt where we had time to visit the pyramids, the Sphinx and see a little of Cairo with its Blue Mosque. Then we headed into the desert regions towards the north coast where we encamped. It was very, very hot and heatstroke was not uncommon among the men. A great hole was dug in the sand as large as a room; over the entrance was hung a raffia curtain for a door over which water was poured continuously so that any air entering the room was cooled. There were also ice boxes to help keep things cool and often patients were slid down the sand way to the entrance and given a bed in the cool room.

We all had to take salt to restore the loss of moisture in our bodies. The night wind was very unpleasant; hot, sandy and laden with hard particles of sand. I remember one sand storm; you could see nothing but a red colour and so all you could do was close your eyes and sit tight until the storm was over. The camels too just crouched down, closed their nostrils, veiled their eyes and waited until the storm blew by. They were quite unperturbed, unlike me, who did not like the sand storm.

Another day I saw a typhoon approaching; it was a great pillar of sand caught up in a high whirl, speeding here and there unpredictably and dangerously for anyone in its path. It could lift great weights off the ground, sweep roofs from walls, blitz tents like handkerchiefs – most unpleasant. I remember seeing something similar at sea when a water spout blew up; the clouds seemed to be united with the sea and this twisting mass of water was caught up and moving across the seascape in a terrifying manner.

Addressing the Troops March 1943

During the day ‘Monty’ used to leave his advance dug out and caravan where he prepared and directed operations and come to address the troops. It was all very informal; we would be called from our tents to a mass meeting where Monty would stand up in his jeep, surrounded by his men. He explained that we were to prepare to sail across from North Africa to Sicily under the protection of such a barrage of fire from the air force and gunners that we could hope to make the crossing in reasonable safety. Beforehand we had to learn about our stations on the landing craft so that we could then move swiftly on to land and find cover. When the invasion began we were shipped across the sea safely under the protection of the air force and then landed using the amphibious craft designed to move on land or sea. The whole operation had to be done very quickly and the enemy was to be pushed back to the north of the island.

Padre Joe in Italy, second from left.

Invasion of Italy from Sicily August / September 1943

"Despite the fierce opposition from the enemy, the Germans retreated to Messina where the Straits separate Italy from Sicily. Syracuse, where we stayed, was an ancient township well known in Roman history. The island was very volcanic, with Mount Etna smouldering away all day, and at night the sky was lit by the red glow of the inner crater.

We soon moved up to Messina and prepared to cross the Straits into Italy, the enemy always being driven before us. Southern Italy proved to be a sunny land with wonderful landscapes just like the backcloth to some great stage play or opera. The towns were very quaint and old, perched on hilltops for safety; the way up was always steep and rocky and used by men, mules and donkeys. The smell of these picturesque towns was something! The men were mostly away at war and the women carried on all the business and could put their hand to anything; field work, building, harvesting, child bearing. I tried to learn Italian with a child’s book and when I got stuck I would ask the Italian women who would laugh and shake their heads! They could not read at all.

By this time the Italians had no stomach for warfare and were anxious to have done with it; they miscalled the Germans and Mussolini. Travelling slowly through the country, as we advanced, I would often sit with the people of an evening in the village or some lonely croft. Their life was very primitive but very effective and the Latin I had learned stood me in good stead and by now I could make myself understood.

One day one of the officers was assigned to take me back to camp after visiting the Gun sites; we had to cross a river in spate and although the troops signalled us not to cross, the Officer, disgruntled by the prospect of having to stay out of camp, just headed right into the water. We immediately hit boulders and made heavy passageway, then in mid stream I felt the truck lift off and we were afloat. Luckily we were thrust toward the opposite shore and was I glad to reach safety!"

Naval Tank Landing Craft at Anzio.

Anzio Beach Head March / May 1944

"Now we were ready to take over the Anzio Beach Head; this was a strip of land which must be held if the Germans were to be beaten back. We made port in our ships under fierce enemy fire and quickly fled north, nearer and nearer the German lines where it was much safer. The men who were wounded hated to be sent back to the port because it was there that the enemy fire fell most heavily. The field hospital was a tent or group of tents very heavily sandbagged around the walls and with little cover overhead. Up front we had to dig in and the men made wonderful trenches and brought many unexpected skills to make them comfortable and even homely.

Our stay there ended up being months, rather than weeks, until it was possible to break forward through the enemy. The range between us was very short and when guns fired on either side, the opposing side could then pinpoint the place with alarming accuracy and we all then knew to take cover. One enemy shell was known as, ‘Moanin’ Minnie’ because of its long whine, heard long before the shell actually fell. Along the beach head were woods and the men forward used to run a long white tape across the woodlands so they could find their way easily back and forth. Unfortunately the enemy discovered the tape and redirected it so that some of our men ran straight into the enemy lines. One man, realising the danger, climbed a tree and sat there, deadly still, while the enemy prowled beneath.

Part of my daily routine was to tour the Gun sites; these were placed in hollow sand dunes or just on the edge of the woodlands. I carried with me my portable record player as the men were always glad of a little distraction. I would read a little from the Bible and then say, “I’ll pray but you keep your eyes skinned.” In the bright sunshine of the early morning the enemy planes used to get directly between us and the sun so that we could not see them coming. The planes would come in with no engines running so all of a sudden they would swoop down out of nowhere with their shell fire and we would have to give them all we had to try and bring them down. There were often planes streaming away into the skies and sometimes a plane which had been shot would spiral down with smoke billowing out or disintegrate totally and fall to the sea. Luckily most of the crews were able to bale out in time with their parachutes.

In spite of all the warfare it was a lovely spot with yellow sand dunes and the shore with the blue waters of the Mediterranean lapping right up to our feet. Some of the men even dared to swim on occasion! I used to be called ‘Jonah’ as it appeared that, wherever I went, the enemy fire would follow! I loved to walk through the woodlands going from gun site to gun site, it was a picturesque route which I had to walk alone, always hoping that I would arrive safely and often trembling at the nearness of the firing. Wild flowers grew there in profusion as well as cyclamen, beautiful in its wild state. The men used to gather wild strawberries and, if they could, make strawberry pie; they were always very generous, sharing whatever they had with me.

I remember one day on my rounds, the Doctor came with me when suddenly we were in the midst of enemy fire. The Doctor and I both threw ourselves simultaneously into a nearby ‘Funk hole’ and when the enemy eventually passed over we lay there, helpless with laughter! On another occasion when the Colonel came to share a meal with us at rough, hewn tables, the enemy, again, suddenly came upon us. With one spontaneous plunge we were all under the table and later rose to hear the Colonel’s cursing and swearing at the enemy. The instinct of self preservation is a wonderful thing!

Monte Cassino rebuilt.

[Photo thanks to the Gap Deciders]

Monte Cassino

"So the weeks passed and ahead lay Monte Cassino, a monastery on the hill, now heavily armoured by the enemy and almost impregnable with mines sown like seeds down the hill and along the level land. Trucks and men fell foul of these mines and thousands of lives and limbs were lost. After much fierce fighting, Monte Cassino eventually fell and we were able to leave the Beach Head and proceed north, following the enemy. From here we were to fight a rearguard action all the way to Rome. Through our field glasses we could even see the enemy retreating from their settled embattlements in farm houses and village sites.

Advance through Italy

Our advance through Italy was in spring time and we had to contend with swollen rivers, broken bridges and rough track roads. Gun Sites were often bogged down in mud. At times we had to use landing craft to cross the rivers and sometimes had to construct pontoon bridges. We grew adept at camping in the mud and taking our food whenever we could settle down for the night. The Colonel we had at that point was a good man but very fiery when he had a drink. He and I got along very well. One night we were installed as HQ in a barn and loft; I slept in the loft with the Officers.

During the night one of the men got up to go to the toilet and as it was extremely cold he thought he would relieve himself from the loft to the outside. Unfortunately the Colonel was having a midnight prowl to see all was well when the urine descended upon him. The poor Officer concerned was hauled down and stood in the kitchen; I crept along, feeling very sorry for the man but not sure whether I should interfere or not. The Colonel called the Officer everything under the sun and besmirched the name of everyone in the man’s family from Adam down.

On another occasion this same Colonel had to visit all the Gun Sites as it was Christmas. He asked me to accompany him as he knew the men would all offer him a drink and knew that, of course, he had to refuse. “Padre, you know my weakness, you come along with me.” The mud was awful and our jeep was often in danger of over-turning, however the Colonel managed to keep us both safe on that particular Christmas tour of the Gun Sites.

Excavation of Pottery

At each stage we had to advance then ‘dig in.’ At one point, Bruce, a young soldier called out. “Stop digging I’ve found ancient pottery!” And war or no war, Bruce somehow had his way and carefully excavated around the pottery until he had assembled a whole collection. Bruce was an odd man; he often went around in a dream like state, spoke with the finest of accents and was obviously highly intelligent. Only Officers were allowed to use the military post so Bruce came to ask me if I could send home his pottery. Like Bruce, himself, the pottery was wrapped in such a dishevelled way that, in the end, I put it all in a wooden ammunition box and sent it back home for him. It was well after the war when Bruce sent me a most beautiful, glossy, illustrated brochure of the restored pottery, which dated back to the third century BC. Bruce may not have been a soldier but he was certainly a fine scholar.

Shot in the Foot

Around this time of rear guard action, one of our majors was cleaning his gun when he shot himself in the foot. This was a dreadful calamity for an Officer; such an accident was deemed a self inflicted wound. The Major came to me and begged that I would speak to the Brigadier on his behalf. I liked the Major; he was a good man and so I went to see the Brigadier who listened, at first sternly, but then sympathetically. In the end arrangements were made to send the Major back for treatment and, later, once his injury was recovered, he was restored to his unit.

At one point during our advance I was with a small contingent of men who were housed in a stone dwelling, badly shelled by enemy fire. During the night one young Officer could not sleep for fear of enemy fire. “Get up and walk around,” he was advised. The Officer, however, could not contain himself, was in danger of becoming ‘Bomb happy’ and, as such, was sent back to the lines. There were one or two men who could not stand the pace and we felt very sorry for them when their nerves gave way completely. Naturally we were all very tense and there were often moments when fear took hold.

Near this house was a place called ‘Hell Corner’; named such because our advancing trucks had to round this corner at high speed to avoid the enemy fire directed at the corner. Tommy, my Batman and driver, and I had spent the night in the shell scarred house and were to leave first thing. Not long after starting out we came under enemy fire; we both leapt from the truck and hid behind some rocks. Tommy got out his cigarettes and handed me one, even though he knew I didn’t smoke. We couldn’t stay there so we had to move; we advanced upon ‘Hell Corner’ in our truck and, on reaching it, we flew round it at high speed followed by bursts of enemy fire. We had made it and all we could do was laugh our heads off! Laughter was most often the most wonderful release of tension after being in tight spots.

Batman Tommy

Tommy became one of my best friends and helpers; he was a railway employee, a gentle soul who never got angry or upset, always helpful and kindly. After the war I used to visit him in Rutherglen; he lived with his mother and two sisters, one of whom was very deaf and the other was prone to fits. He loved a girl from the Isle of Man but, because of his family responsibilities, he never married and Frances and I were always sorry about this. Tommy used to come through to see us in Haddington and Frances liked him immensely. He sent us a lovely singing jug for our wedding; it played ‘Auld Lang Syne’ Later in the years after the war when we would have great reunions in Edinburgh and Haddington I would always play the jug, ‘Should auld acquaintance be forgot.’

Tommy was a fine man; he had a slight stutter which was quite attractive. My only complaint was when he ate the army fish and breathed fish all over me in our stuffy truck until I was demented! This wasn’t quite so bad as when I had a relief driver to take me through the bomb craters to visit the men; I just had to open the window as there seemed to be the smell of the dead in the truck. “Not the dead, Sir,” came the reply from the driver, “only my feet!” There was nothing I could do about that one!

Rome and beyond June 1944

Once we had successfully driven the enemy right back through Italy as far as Rome we were retired to Israel for three months rest.

When we took ship again we headed for a landing at Marseilles where the ‘Mistral’ was blowing, a most unpleasant wind. On landing I had my old army trunk and, instead of landing it on the boat alongside it was tipped into the sea. Luckily we were almost in the harbour where an American diver took pity on me and dived to recover my trunk. I had to stretch out my clothes in the wind along with my bible in the hope of drying them; the ‘Mistral’ did this wonderfully well and I was, amazingly, still able to use my Bible.

Jock, Padre Joe and Tom in Germany.

Probably in the Hartz mountains.

Germany March 1945

"From Marseilles we journeyed north until we came to the German border where we were engaged again in arms before we could cross the River Elbe. The town colony was in ruins, cattle lay dead and stinking in the fields and other milking cows lowing piteously as there was no one to relieve them of their milk. The fighting continued against Cologne and we left it an absolute shell; it was terrible to see the majestic cathedral standing like a great skeleton, reaching up naked towards the sky.

By this stage ‘D Day’ had come and gone and our troops were advancing from the north. Our army finally reached Wernigerode, a delightful German town, where the German women begged us to take them with us before the Russians entered the town. It transpired that we had advanced too far and were now in Russian Territory. We could not take the women and it was a sad sight to see their fear.

By this stage the German might was crumbling, they knew defeat was near and so ‘V Day’ came and we were sent to the Harz Mountains to two lovely little village towns, Hannenklee and Bockweisse. The land was beautifully wooded with fine lakes for boating and swimming. It was an ideal spot and we enjoyed it. We were forbidden to fraternise with the Germans but, bit by bit, this had to be changed. At war, our men had only one thought, to get things over with and return home. But now, in this fragile ‘peace’ the men had thoughts of women and I was sad to see how both our men and the German women took advantage of this. We lived for a time in a German Castle (Schloss) where there was a wonderful piano.

I was now attached to the Lanarkshire Yeomanry, a heavy gunner contingent with very fine men and Officers. I hated to be too near when the guns were firing; the sound was horrifying and the gunfire often passed directly overhead and always unexpectedly. Gunfire of aircraft at close proximity still produce a reaction in me that is still quite shattering even years on. The Lanarkshire Yeomanry instigated the writing of their war experiences and got the Germans to print it. I was asked to write the epilogue and quoted one of Rudyard Kipling’s poems, appropriately I hope."

Tom, Joe and Jock (from Haggs) in Germany.

End of the War

"In time the atom bomb was dropped and so brought about the end of the Japanese War; thousands of prisoners were set free to tell their tale of great suffering and hardship. Many had lost their lives in confinement, many returned sick and blinded and all were half starved. It was a sad tale and there are still those today who can never forget or forgive the atrocities the Japanese perpetrated upon their enemies. VJ Day was soon followed by VE Day and months passed in a weird peace time atmosphere until we were at long last sent back to Britain. I was asked if I would like to stay on in the army and would have been well off financially, however I had had enough of army life and was glad to return to ‘Civvie Street’ and home in Dunfermline."

The Reverend Joe Ritchie in his later years.