Evacuees

Pre-War Anxieties

The destructive power of modern aircraft, graphically illustrated by the Nationalists and their German allies during the Spanish Civil War, created an atmosphere of considerable popular and official anxiety in the UK prior to 1939. The example provided by the bombing of Guernica in Northern Spain was widely known and, should war return, the authorities anticipated similarly destructive attacks being made on Britain’s urban areas. It was commonly held that bombers could literally flatten whole cities and inflict huge civilian casualties in the process. Being keenly sensitive to this possibility, the authorities planned accordingly. Preventative measures taken included contingency plans to evacuate as many of the urban young as possible to the safety of the less threatened countryside.

Lady Helen O’Brien with evacuees at Broxmouth House, Dunbar.

Edinburgh Evacuees

When Germany invaded Poland on 1st September 1939 the official evacuation scheme was launched in Edinburgh and 26,000 children (just over 40% of those eligible) were taken out of the city. They were taken to centres anywhere from Inverness to the Borders, including to East Lothian. By March 1940, even though 100 children were being sent from Edinburgh every week, only 9,968 remained outside the city. Clearly the effects of the Phoney War and the pull of home overcame many parents' concerns.

Eyewitness: Edinburgh youngster David Campbell remembers his evacuation to Haddington:

When Germany invaded Poland on 1st September 1939 the official evacuation scheme was launched in Edinburgh and 26,000 children (just over 40% of those eligible) were taken out of the city. They were taken to centres anywhere from Inverness to the Borders, including to East Lothian. By March 1940, even though 100 children were being sent from Edinburgh every week, only 9,968 remained outside the city. Clearly the effects of the Phoney War and the pull of home overcame many parents' concerns.

Eyewitness: Edinburgh youngster David Campbell remembers his evacuation to Haddington:

Evacuation

“How and when my parents decided to have their children evacuated, I do not know – in those days children were not consulted about these matters. We were probably told we would be sent to a safe place in the country; it would be a sort of adventure holiday for a short time. We accepted that our parents knew best, and they felt that the authorities knew best. My sister, Elspeth, aged 13, my brother, John, aged 11, and myself, David, aged 9 years, would all be together so we would still be in the family – after all the leaflet from the Council said that every effort would be made to keep families together.

The order was given by the government at 11:07am on 31st August to ‘Evacuate Forthwith’.

I think that it was on the 1 September that we three children left our home at Tollcross, Edinburgh, carrying our luggage, on our way to school at the appropriate hour in the morning. We probably went by tramcar to Bruntsfield where our schools were; I don’t think that we would have had to walk that half mile with all our bags and bundles. Once we arrived at school we were put into classrooms and there we sat, surrounded by cases, rucksacks and carrier bags, for a very long, boring forenoon. Every so often a teacher would come in with a list and tick us off. We had luggage labels tied on us showing our names, ages, and schools, then we were counted again, and again. About mid-morning we were given the customary bottle of school milk and a banana. It must have been about midday we were all led outside and formed up into a long crocodile for the walk to Morningside Station and the train. The distance from school to station was about a mile and fortunately the weather was dry. There were teachers and helpers acting as sheepdogs all along the column and, although they had been requested not to, we were followed by some parents wanting to see where their lambs were going: no one had told us or them - I suppose if our destination was kept secret the Germans would not know where to find us! We reached the station, were put into carriages, and set off, with no idea of where we were going.

Arriving at Haddington

After about an hour’s journey, we stopped at a station, disembarked, and formed up into our crocodile again, carrying our gas masks, cases, etc. We still did not know where we were and the name boards at the station had been taken down to confuse any invaders. We then walked into the town, a distance of about a quarter of a mile, and came to the Town House; somehow the word was passed along the line that we were in Haddington!

I suppose we were given food of some kind and counted yet again. Each of us was then given a brown paper carrier bag; this contained rations for the next two days. I don’t remember all it contained, but I do recall it held a tin of corned beef and a bar of chocolate, along with other food – it was something else for us to carry. My sister, brother and I were put into a group of about thirty children; I did not know any of the others, they may not have been from our school, there was no one from my class anyway. In charge of us was a billeting officer with a list; in our case, his name was Mr Harris.

We set off from the hall, following Mr Harris along Market Street, Newton Port and up Victoria Park. When we came to a house that was on the list we would stop, Mr Harris would knock on the door and the lady of the house would come out, look over the children and make her selection. Children wearing the uniform of a private fee-paying school were most popular, good-looking children came next in favour; most housewives were looking for girls. Our party did not call at farms but I believe that farmers were on the lookout for big strong boys. No child was ever asked if he would like to stay at that house or with that lady. I have read books written by people who as children were evacuated all over Britain and the same selection process seems to have been used everywhere. No evacuee has ever forgotten the humiliation of taking part in a type of cattle market.

We came to the house of the local fire master – a Mr and Mrs Lee-Hogg, a middle-aged couple with no children. Mrs Lee-Hogg picked my sister and another girl of the same age, and took them off. Our numbers were thinning out a bit by the time we reached Vetch Park. The first house was occupied by Mr and Mrs Allen, again a middle-aged couple with no children; he was a house painter whose family owned a painter’s business in Sidegate. Mrs Allen seemed a bit disappointed – she wanted two girls, but there were none left so she took my brother and me but said we would have to do girls’ work in the house.

After he had shed all his charges, Mr Harris had to go round the route again to complete the paper work; this time he had his dog with him, a Border terrier, which was a nice distraction for the children. The paper work was done in the best room, furnished very nicely with a carpet and a piano; Mrs Allen gave piano lessons. Later we were told never to go into that room, and we never did. We were told by Mrs Allen that she would not do our laundry, so every week my sister had to make up a parcel and post the washing home to our mother. Mr Archie Allen was an ARP warden which took him out every evening. As he was at work every day, we did not see a lot of him, but he sometimes took us for walks on a Sunday. He had been a military policeman in the First World War and his uniform still hung in a cupboard in the house. We were well looked after by the Allens and had not much to complain about.

School And Summer Holidays

Quite near Vetch Park was the Christie Girls Home. I do not know much about this Home, but in the grounds was a small two-classroom school; this is where I went for the rest of that school year. It was only evacuees in the classes, I have no idea where the girls from the Home went.

During the summer holidays, four of the teachers from the Knox Institute organised a camp for the evacuee boys. As far as I can remember the teachers were Frank McLeod, who taught gym, Mr Bennet (maths?), and two ladies who looked after the catering. They had borrowed tents from somewhere and our campsite was near Gifford. There were some snags as the length of the tent poles did not always match the height of the bell tents, also it rained - it rained a lot. Eventually we got flooded and had to move into the attic of the shepherd’s cottage nearby. Shortly after the camp, both men teachers went into the army and I think I heard that Frank McLeod was killed; I believe he was a Haddington man.

By sheer coincidence, with my brother, I found a job during the holiday helping a Mr McLeod who, I think, was the father of Frank McLeod the gym teacher. Old Mr McLeod had a large garden – I think it was a commercial project – and he also kept a pig. We would “help” him in the garden. Every two or three days, he would push a large wheelbarrow round certain houses to collect food waste for his pig; my brother and I went with him to collect pails of waste and empty it into the barrow. We were not paid much, but I don’t think our efforts were worth any more.

I Move Homes

After we had stayed with the Allens for about eight months, Mrs Allen told us she had not been keeping well and the doctor had advised her to stop fostering evacuees. It had been arranged for us to go to a new home in Glebe Terrace; we were to stay with a Mrs Spowage, a widow with three children living at home. Her eldest son, Fraser, had the reputation of a tear-away; he was said to be a very good singer, but I never heard him sing. I saw his death in The Scotsman a few years ago, and learned that he was a past Provost of Haddington.

At the end of Glebe Terrace there was a gate into a field. We would go through the gate, across the field and out at Lydgait, near the cattle market; this made a good shortcut to and from school. I was now a pupil at the Knox Institute primary school and was mixed in with local children, including some of the mystery girls from the Christie Home. I must have done quite well there because remember I won a prize at the end of the year.

We were not the first evacuees that Mrs Spowage had homed. Many evacuee children were taken back home when no bombs fell on the capital. When Mrs Spowage told us that she had been advised by the doctor to give up fostering evacuees, I was not very sorry; my brother seemed to have fitted into her household but, maybe because I was the youngest, I never felt accepted by the others.

Runaways

Some children ran away from their foster homes – not too difficult as all they did was get on the first bus to Edinburgh. Two brothers who were billeted with a local doctor’s family did just that; the story circulated among evacuees was that they had run away because they were “made to eat tattie peelings”. I never forgot this, until I realised that all that had happened was that they were given potatoes cooked with their skins on; they had never met such a thing before. A few years ago I met a woman who had come to live in West Linton - Dr Mary Barlee - she was the daughter of Dr McLean who had fostered the boys; she confirmed my conclusions about the tattie skins – they had frequently eaten potatoes cooked in their jackets! How to start an evacuee horror story!

About this time my sister went home to Edinburgh; she was of school leaving age and was going to a commercial college in town to learn shorthand and typing. During the thirteen months she had spent in Haddington, she had stayed in five different houses; this was not unusual, there was constant movement of evacuees.

I Move Home Again

The next house my brother and I were sent to was occupied by a Mrs Watling, a widow with no children. She had been fostering evacuees from the start and had a moving population of children; there was a boy there I knew from school– his sister had gone home like mine. The house, 52(?) Court Street, had no electricity and this one had an outside toilet. We soon learned from the other boy, Ronnie Hannay, that Mrs Watling owed money to shops in the town so the more evacuees she could fit in the better her income. At one time while we were there, she let the second bedroom to a soldier and his wife, and moved herself into the bedroom beside the three boys.

At this time my class moved into the new modern building of the Knox Institute. The one drawback was that we would have the terror teacher, a Miss Shaw, known of course to the pupils as Tattie Shaw. However, I got on very well with the dreaded Tattie Shaw and had no trouble with her.

The Bombing Of Haddington

During my stay in Haddington, we had air raids; the sirens would go but we did or did not take cover and often, after an hour or two, the all clear would moan. On the 3 March 1941, bombs were dropped on Haddington. German bombers returning from blitzing Clydebank dropped unused bombs; they may have seen a light or something to indicate a target but did not intend to take the bombs back to base or drop them in the North Sea. 1. Six bombs were dropped on the town, one in Market Street on the opposite side of the street and only about 150 yards from when I was staying. My brother had gone to the cinema that night alone – that was not unusual in those days. When the sirens went, a notice would be flashed on the screen and anyone who wanted to leave to take cover would do so. One bomb fell only twenty yards from the cinema and the building was evacuated. My brother had to make his way past the burning buildings, walking through broken glass, back to the house. We did not have an air raid shelter, but neighbours came and took us to their safer room; on the way, I looked up – the sky was bright red with sparks from the burning houses, but we came to no harm. Next morning we went out to see the damage and realised how lucky we had been.

I Go Home To Edinburgh

Not long after this, my brother contracted scarlet fever and was taken off to the fever hospital; I, of course, was in quarantine. When my brother came home, it was decided that, as he was approaching school leaving age, he should be taken back home to Edinburgh. So Ronnie went back home and I was left on my own. At that time my mother came to visit me. I was not looking forward to a new intake of strangers into the house, and having to share a bed with an unknown boy; I had no trouble persuading my mother, and went home with her there and then. I had been an evacuee in Haddington for two years."

1. This is unlikely to have been the case as the dates of the Clydeside Blitz and the Haddington attack are different.

[David Campbell, 15 April 2015]

“How and when my parents decided to have their children evacuated, I do not know – in those days children were not consulted about these matters. We were probably told we would be sent to a safe place in the country; it would be a sort of adventure holiday for a short time. We accepted that our parents knew best, and they felt that the authorities knew best. My sister, Elspeth, aged 13, my brother, John, aged 11, and myself, David, aged 9 years, would all be together so we would still be in the family – after all the leaflet from the Council said that every effort would be made to keep families together.

The order was given by the government at 11:07am on 31st August to ‘Evacuate Forthwith’.

I think that it was on the 1 September that we three children left our home at Tollcross, Edinburgh, carrying our luggage, on our way to school at the appropriate hour in the morning. We probably went by tramcar to Bruntsfield where our schools were; I don’t think that we would have had to walk that half mile with all our bags and bundles. Once we arrived at school we were put into classrooms and there we sat, surrounded by cases, rucksacks and carrier bags, for a very long, boring forenoon. Every so often a teacher would come in with a list and tick us off. We had luggage labels tied on us showing our names, ages, and schools, then we were counted again, and again. About mid-morning we were given the customary bottle of school milk and a banana. It must have been about midday we were all led outside and formed up into a long crocodile for the walk to Morningside Station and the train. The distance from school to station was about a mile and fortunately the weather was dry. There were teachers and helpers acting as sheepdogs all along the column and, although they had been requested not to, we were followed by some parents wanting to see where their lambs were going: no one had told us or them - I suppose if our destination was kept secret the Germans would not know where to find us! We reached the station, were put into carriages, and set off, with no idea of where we were going.

Arriving at Haddington

After about an hour’s journey, we stopped at a station, disembarked, and formed up into our crocodile again, carrying our gas masks, cases, etc. We still did not know where we were and the name boards at the station had been taken down to confuse any invaders. We then walked into the town, a distance of about a quarter of a mile, and came to the Town House; somehow the word was passed along the line that we were in Haddington!

I suppose we were given food of some kind and counted yet again. Each of us was then given a brown paper carrier bag; this contained rations for the next two days. I don’t remember all it contained, but I do recall it held a tin of corned beef and a bar of chocolate, along with other food – it was something else for us to carry. My sister, brother and I were put into a group of about thirty children; I did not know any of the others, they may not have been from our school, there was no one from my class anyway. In charge of us was a billeting officer with a list; in our case, his name was Mr Harris.

We set off from the hall, following Mr Harris along Market Street, Newton Port and up Victoria Park. When we came to a house that was on the list we would stop, Mr Harris would knock on the door and the lady of the house would come out, look over the children and make her selection. Children wearing the uniform of a private fee-paying school were most popular, good-looking children came next in favour; most housewives were looking for girls. Our party did not call at farms but I believe that farmers were on the lookout for big strong boys. No child was ever asked if he would like to stay at that house or with that lady. I have read books written by people who as children were evacuated all over Britain and the same selection process seems to have been used everywhere. No evacuee has ever forgotten the humiliation of taking part in a type of cattle market.

We came to the house of the local fire master – a Mr and Mrs Lee-Hogg, a middle-aged couple with no children. Mrs Lee-Hogg picked my sister and another girl of the same age, and took them off. Our numbers were thinning out a bit by the time we reached Vetch Park. The first house was occupied by Mr and Mrs Allen, again a middle-aged couple with no children; he was a house painter whose family owned a painter’s business in Sidegate. Mrs Allen seemed a bit disappointed – she wanted two girls, but there were none left so she took my brother and me but said we would have to do girls’ work in the house.

After he had shed all his charges, Mr Harris had to go round the route again to complete the paper work; this time he had his dog with him, a Border terrier, which was a nice distraction for the children. The paper work was done in the best room, furnished very nicely with a carpet and a piano; Mrs Allen gave piano lessons. Later we were told never to go into that room, and we never did. We were told by Mrs Allen that she would not do our laundry, so every week my sister had to make up a parcel and post the washing home to our mother. Mr Archie Allen was an ARP warden which took him out every evening. As he was at work every day, we did not see a lot of him, but he sometimes took us for walks on a Sunday. He had been a military policeman in the First World War and his uniform still hung in a cupboard in the house. We were well looked after by the Allens and had not much to complain about.

School And Summer Holidays

Quite near Vetch Park was the Christie Girls Home. I do not know much about this Home, but in the grounds was a small two-classroom school; this is where I went for the rest of that school year. It was only evacuees in the classes, I have no idea where the girls from the Home went.

During the summer holidays, four of the teachers from the Knox Institute organised a camp for the evacuee boys. As far as I can remember the teachers were Frank McLeod, who taught gym, Mr Bennet (maths?), and two ladies who looked after the catering. They had borrowed tents from somewhere and our campsite was near Gifford. There were some snags as the length of the tent poles did not always match the height of the bell tents, also it rained - it rained a lot. Eventually we got flooded and had to move into the attic of the shepherd’s cottage nearby. Shortly after the camp, both men teachers went into the army and I think I heard that Frank McLeod was killed; I believe he was a Haddington man.

By sheer coincidence, with my brother, I found a job during the holiday helping a Mr McLeod who, I think, was the father of Frank McLeod the gym teacher. Old Mr McLeod had a large garden – I think it was a commercial project – and he also kept a pig. We would “help” him in the garden. Every two or three days, he would push a large wheelbarrow round certain houses to collect food waste for his pig; my brother and I went with him to collect pails of waste and empty it into the barrow. We were not paid much, but I don’t think our efforts were worth any more.

I Move Homes

After we had stayed with the Allens for about eight months, Mrs Allen told us she had not been keeping well and the doctor had advised her to stop fostering evacuees. It had been arranged for us to go to a new home in Glebe Terrace; we were to stay with a Mrs Spowage, a widow with three children living at home. Her eldest son, Fraser, had the reputation of a tear-away; he was said to be a very good singer, but I never heard him sing. I saw his death in The Scotsman a few years ago, and learned that he was a past Provost of Haddington.

At the end of Glebe Terrace there was a gate into a field. We would go through the gate, across the field and out at Lydgait, near the cattle market; this made a good shortcut to and from school. I was now a pupil at the Knox Institute primary school and was mixed in with local children, including some of the mystery girls from the Christie Home. I must have done quite well there because remember I won a prize at the end of the year.

We were not the first evacuees that Mrs Spowage had homed. Many evacuee children were taken back home when no bombs fell on the capital. When Mrs Spowage told us that she had been advised by the doctor to give up fostering evacuees, I was not very sorry; my brother seemed to have fitted into her household but, maybe because I was the youngest, I never felt accepted by the others.

Runaways

Some children ran away from their foster homes – not too difficult as all they did was get on the first bus to Edinburgh. Two brothers who were billeted with a local doctor’s family did just that; the story circulated among evacuees was that they had run away because they were “made to eat tattie peelings”. I never forgot this, until I realised that all that had happened was that they were given potatoes cooked with their skins on; they had never met such a thing before. A few years ago I met a woman who had come to live in West Linton - Dr Mary Barlee - she was the daughter of Dr McLean who had fostered the boys; she confirmed my conclusions about the tattie skins – they had frequently eaten potatoes cooked in their jackets! How to start an evacuee horror story!

About this time my sister went home to Edinburgh; she was of school leaving age and was going to a commercial college in town to learn shorthand and typing. During the thirteen months she had spent in Haddington, she had stayed in five different houses; this was not unusual, there was constant movement of evacuees.

I Move Home Again

The next house my brother and I were sent to was occupied by a Mrs Watling, a widow with no children. She had been fostering evacuees from the start and had a moving population of children; there was a boy there I knew from school– his sister had gone home like mine. The house, 52(?) Court Street, had no electricity and this one had an outside toilet. We soon learned from the other boy, Ronnie Hannay, that Mrs Watling owed money to shops in the town so the more evacuees she could fit in the better her income. At one time while we were there, she let the second bedroom to a soldier and his wife, and moved herself into the bedroom beside the three boys.

At this time my class moved into the new modern building of the Knox Institute. The one drawback was that we would have the terror teacher, a Miss Shaw, known of course to the pupils as Tattie Shaw. However, I got on very well with the dreaded Tattie Shaw and had no trouble with her.

The Bombing Of Haddington

During my stay in Haddington, we had air raids; the sirens would go but we did or did not take cover and often, after an hour or two, the all clear would moan. On the 3 March 1941, bombs were dropped on Haddington. German bombers returning from blitzing Clydebank dropped unused bombs; they may have seen a light or something to indicate a target but did not intend to take the bombs back to base or drop them in the North Sea. 1. Six bombs were dropped on the town, one in Market Street on the opposite side of the street and only about 150 yards from when I was staying. My brother had gone to the cinema that night alone – that was not unusual in those days. When the sirens went, a notice would be flashed on the screen and anyone who wanted to leave to take cover would do so. One bomb fell only twenty yards from the cinema and the building was evacuated. My brother had to make his way past the burning buildings, walking through broken glass, back to the house. We did not have an air raid shelter, but neighbours came and took us to their safer room; on the way, I looked up – the sky was bright red with sparks from the burning houses, but we came to no harm. Next morning we went out to see the damage and realised how lucky we had been.

I Go Home To Edinburgh

Not long after this, my brother contracted scarlet fever and was taken off to the fever hospital; I, of course, was in quarantine. When my brother came home, it was decided that, as he was approaching school leaving age, he should be taken back home to Edinburgh. So Ronnie went back home and I was left on my own. At that time my mother came to visit me. I was not looking forward to a new intake of strangers into the house, and having to share a bed with an unknown boy; I had no trouble persuading my mother, and went home with her there and then. I had been an evacuee in Haddington for two years."

1. This is unlikely to have been the case as the dates of the Clydeside Blitz and the Haddington attack are different.

[David Campbell, 15 April 2015]

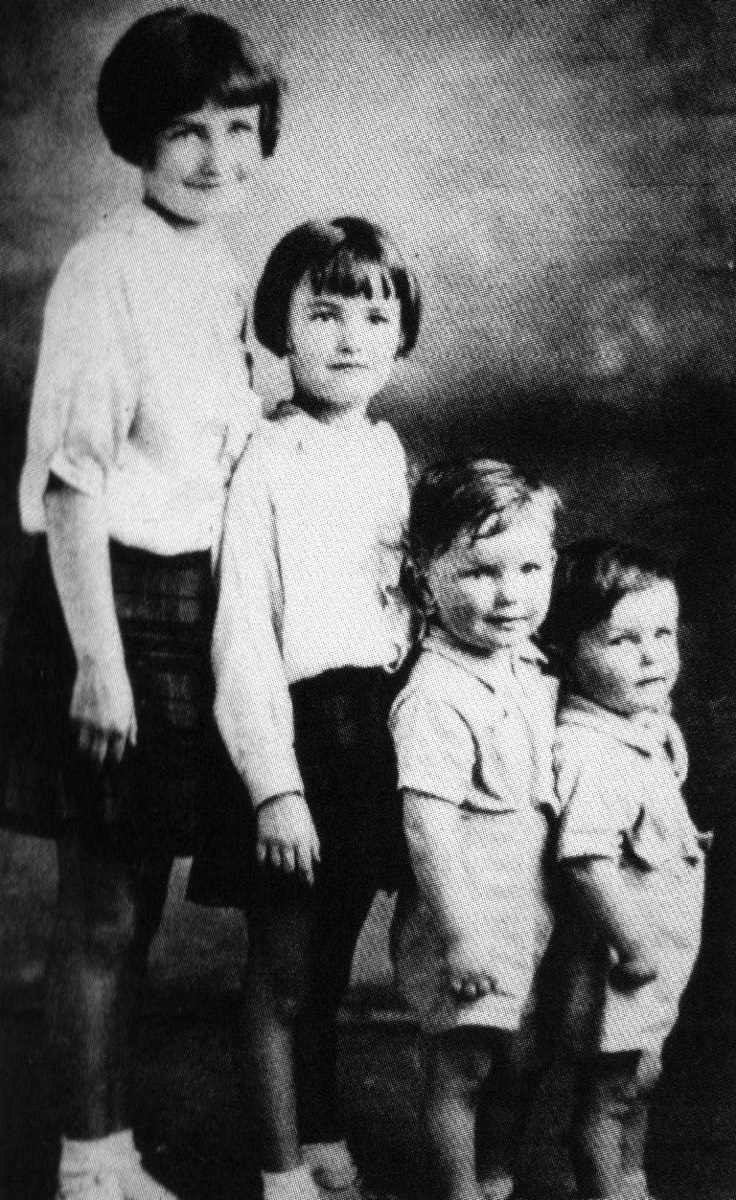

Margaret, Doreen, Norman and Donald King.

Luffness House, Aberlady.

Clash Of Cultures

The evacuation of so many city children to the countryside was not without its surprises. City children were not used to the quiet, conservative and sometimes primitive ways of country life: farming families were little used to what they often found to be dirty and ill-behaved city children. It was a distinct clash of cultures in the days when town and country were so distinctly different and less frequently mixed. However, as David Campbell’s account illustrates, many of those who ‘fostered’ evacuees were happy to make use of tadditional pairs of hands whether around the house or out on the farm.

Luffness House

While most evacuees were treated as well as circumstances allowed, there were cases when the experience of evacuation could be thoroughly unpleasant. Early in the war Luffness House was taken over by a Naval Orphanage Trust from Edinburgh, known as the Mayfield School. From the following account it would appear that the school’s outpost at Luffness was run along strict lines, perhaps with faint echoes of Nelson’s day! Four siblings, Margaret, Doreen, Peter and Donald King were evacuated to their aunt’s in Airdrie in September 1939 but soon returned to their mother in Portsmouth. In 1942, when the bombing of Portsmouth started in earnest, the children were once more evacuated from the city. As before they headed north but this time were taken to Aberlady and ultimately to Luffness House. There they found some 100 to 150 other evacuees.

The evacuation of so many city children to the countryside was not without its surprises. City children were not used to the quiet, conservative and sometimes primitive ways of country life: farming families were little used to what they often found to be dirty and ill-behaved city children. It was a distinct clash of cultures in the days when town and country were so distinctly different and less frequently mixed. However, as David Campbell’s account illustrates, many of those who ‘fostered’ evacuees were happy to make use of tadditional pairs of hands whether around the house or out on the farm.

Luffness House

While most evacuees were treated as well as circumstances allowed, there were cases when the experience of evacuation could be thoroughly unpleasant. Early in the war Luffness House was taken over by a Naval Orphanage Trust from Edinburgh, known as the Mayfield School. From the following account it would appear that the school’s outpost at Luffness was run along strict lines, perhaps with faint echoes of Nelson’s day! Four siblings, Margaret, Doreen, Peter and Donald King were evacuated to their aunt’s in Airdrie in September 1939 but soon returned to their mother in Portsmouth. In 1942, when the bombing of Portsmouth started in earnest, the children were once more evacuated from the city. As before they headed north but this time were taken to Aberlady and ultimately to Luffness House. There they found some 100 to 150 other evacuees.

Eye-witness: Doreen Seagrave (né King)

Doreen’s account is long but deserves quoting at length as it paints a strong and very evocative picture of an evacuee far from home.

Bombed Out In Portsmouth

“Our father had been killed (on Russian convoys, 31.1.1942) on HMS Belmont [built in Newport News in 1918 and handed over as part of Lend Lease]. He had joined [the navy] as a boy aged sixteen on 3.11.1905 and his real time started when he was eighteen. My mother was born in Airdrie and put into service aged eleven as a scullery maid, mounting up through the rank and file to become companion to the lady of the house. We were bombed out three times, losing most of our possessions. Once we were buried alive for two days and three nights, because the Air Raid Wardens were told we had moved out just prior to the land mine demolishing a crescent of fine houses.

The furniture van had left and Mum was making a final check that everything was left clean and tidy when the siren sounded just after the bombing started. Mum shepherded us into the Anderson Shelter in the garden, hence the mistake by the neighbours who were rescued. It was a German Shepherd dog, belonging to one of the wardens, that kept returning to the rubble and whining that saved us. They decided to dig down and just verify, for their own peace of mind, that there was nothing. Mum was already a widow.

Evacuated To Airdrie Then To Luffness

At the outbreak of hostilities we were evacuated to my mother’s sister in Airdrie [but] Mum removed us back to Portsmouth. By this time the false war had ended and the bombing began in earnest in 1942. How it was arranged I have no idea. All I know is that we were collected by a tall gentleman in civvies. He had beautiful silver hair and a moustache. He saw to our every need, we wanted for nothing as far as comfort went. The entire train journey was by private coach. We did find out that he was a Naval Officer, though he spoke very little. I know he carried some sort of important papers which he produced when requested, causing the person’s attitude to change dramatically.

It was dark when we finally arrived at Aberlady and were duly handed over to Matron, bewildered, tired, frightened, the two boys clinging to Margaret and I. We tried so hard to be brave. The first night we were placed in a room with four beds and told we would be placed properly the next day, which scared us even more. It was the fear of the unknown. We were woken quite early, about seven o’clock, told to wash and dress and were taken down to breakfast. To our eyes the place was overpowering: large, massive archways, doors, rooms, long dark corridors. There seemed to be an awful lot of other children, probably about one hundred to one hundred and fifty. My brother, Peter, and I reckoned they were all from England. We can’t recall any Scottish children at all. [Later Doreen learnt that many of the children were actually from Edinburgh.]

After breakfast we were taken up to the dispensary where we were well and truly given the once over by the local doctor, checked for head lice, etc. I warranted a lot of attention from him because I had double mastoids since I was three, had had quite a few operations and the ears were still weeping. The general opinion was that I would need keeping an eye on! We were then separated, the two boys taken upstairs to the males' dormitories and Margaret and I to the female dormitories.. Though they were called dormitories, they were more like rooms, with four or five beds in each. There was usually two windows in each room, each in an alcove with bars on the windows. A nurse usually had a room at the top of each stairway, supposedly to make sure there was no fraternising between the boys and the girls. There was one toilet and one bathroom on each floor.

Fitting In, Food And Church

The other children had been at Luffness for some time. We were the strangers, the interlopers, so we were given a hard time. On the whole the children were quite hateful to each other. Our dining and playroom was very large, tables were solid with a ledge running all round underneath. Seating was on long benches. The meals were very basic and pretty disgusting. One item in particular, served fairly regularly, was brown potted meat which we all hated, so we used to slide it off our plates and hide it on the ledge.

Twice a day we walked to and from school [in Aberlady] in a crocodile: wet days through the grounds; dry and sunny days along the estuary. On Sundays we walked to church in Gullane. After church we had lunch and afterwards we had to memorise a hymn, word perfect, before we were all allowed out to play. Sunday was the only day we were supposedly allowed into the grounds. School holidays were the only other time, but not on a daily basis.

School

I was always in trouble at Aberlady School by going into the boys’ playground to play football. One teacher in particular always reported me but the others turned a blind eye. Anyway, I would get six of the best, on each hand, with a strap: oh, what a medicine/punishment that was! The ends used to curl round your fingers no matter how hard you pressed your fingers together. You held your hands out, straight in front of you, one hand upon the other, for the first six, then reverse the hands for the second six.

Bed Wetting And ‘Elastic Parade’

Some of the youngest children used to wet their beds which was a punishable offence. Every morning we had to throw our beds open to air while we did our ablutions. Then we had to make them. Margaret and I hurried to do ours, then we would rush upstairs to help our young brothers who sometimes wet their beds. We would put the top sheet on the bottom, the wet sheet on top, trying to hide the fact when the nurse checked or they were punished. The girls’ knickers were the bloomer type, navy blue with elasticated legs and waistband. Boys’ socks were held up by elastic garters. Every morning we had ‘elastic parade’: in two lines, boys one side, girls the other, and Matron would move slowly along the lines, pinging at each waistband and knicker leg, then check the boys’ legs for their ‘ping’. If you did not ping properly you were punished. My brothers frequently lost a garter, so either Margaret or I would make a new one by taking elastic from our knickers. Our elastic got so tight it used to cut into our flesh which was extremely painful. Fortunately we had clean knickers once a week with new elastic in.

A dear old, bent lady, called Miss Harvey, saw to the mending of our clothes and the replacement of the elastic. I remember the room was quite large and very spooky, full of old sewing machines, jumble, two or three suits of armour. On the floor was a Bengal Tiger skin. The only light in the room was by Miss Harvey’s work station. It was like an oasis in the desert. She was so kind to us children, sneaking the odd piece of elastic to us and, wonders of wonders, a sweetie!

Scrumping And Being Left-Handed

At night we used to creep out into the grounds to the huge glasshouses. Oh, what a haven of delight they were: peaches, grapes and other exotic fruits. We had one pane of glass that we could remove after we had removed the putty, then the smallest (usually myself) wriggled through and scrumped. We resealed the glass with chewing gum we used to pick up off the streets. We carried our ill-gotten gains back to our dormitory in our knickers. We always shared with our friends, handing out our harvest straight from our knickers into our mouths. Very hygenic!

I was fortunate enough to win a prize for handwriting which was presented by Mrs Hope [wife of the owner]. The teacher happened to mention to her that I was left handed. Horror, shock, I sensed that I had done something wrong but could not understand what till I returned to school after the recess. My left-hand arm was pulled up behind my back, my wrist was wired, the wire was hooked around my back so that each time I tried to use my left hand the wire cut into my neck. This soon became very sore with a deep red welt. Apparently I was a child of the devil... The only time at school it was removed was for knitting or sewing. We knitted balaclavas, gloves or squares for blankets depending on our proficiency. I, of course, knitted left-handed. The teacher would periodically stand over me bringing the edge of the ruler down sharply across my left hand. It didn’t work: I still knit left-handed though I now use my right hand for most other things.

Initiation

To be accepted by the other children we had an initiation test to pass. We had to climb a circular stairway in the bell tower, jump and grab the rope and slide down. Margaret and I had to do it twice, so Peter and Donald were accepted. It was terrifying. I do not know what the actual drop was, but it seemed like a hundred feet! I believe the bell had been taken down for the war effort.

D-Day Preparations

Prior to the Normandy Landings we were forbidden to go into the grounds: we could not understand why and no explanation was given to us. For a period of three to four days we could hear this deep rumble, the ground shook and the air felt and tasted strange almost metallic. Margaret and I decided to find out why and sneeked into the grounds. By climbing a tree and looking over a wall we saw a continuous stream of tanks, lorries canvas covered, gun carriages and motor cyclists. Outriders, I think they were called. Going further into the grounds we saw tents, a town of khaki, muddy brown canvas. Men were speaking in strange tongues. Some had turbans on their heads, dark skinned and flashing eyes. We thought they had the ‘evil eye’ and would steal our souls, but they turned out to be the best of them all. They loved us children and never, by word or deed, harmed us. They told the most magical stories and we came to love them dearly, our Indian Princes, as that is how we thought of them.

The American troops we had to be very careful of, if they gave you candy they expected something of you in return. The black Americans always seemed to be singing, deep haunting music that caused goose-bumps. The troops used to give us sweets and tins of fruit, huge slabs of chocolate, dark and bitter, but how we loved it. As we had no tin-opener we used a sharp rock and a bit of slate to open these tins, We had to be very careful because you could slice your hand open. We remember metal railings being taken down and laid on the ground so that the tanks could move around the grounds, the ground was so soft, almost swampy in places.

Bath Night And High Jinks

Bath night was always Sunday, ready for school on the Monday. Two to a bath, older children helped to bathe the young ones. They were then taken off to bed by Nurse. The older developing girls were next. Our hair was washed as we sat in the bath, rinsed by pouring clean water out of enamel jugs. The older boys used to try to scare us at night by creeping into our rooms covered by a sheet lit underneath by a torch or a candle making weird noises and rattling bits of chain, etc. To get our own back we used to strip their beds and remake them, apple pie, which consisted of doubling the top sheet and making it look like two sheets. Hence they couldn’t stretch out properly and so had to remake their beds.

Christmas

Leading up to Christmas all parcels were kept in a locked room. On Christmas Day we were taken into the room, made to sit cross-legged and Matron and two nurses called out the names on the parcels and we had to go forward to receive them. It was very embarrassing for us as nearly all the parcels were addressed to us. Some of the children had nothing, which made it worse, they looked so sad and forlorn or pretended they did not care by being very brash. We received beautiful hand-made toys, for the boys wooden tractors, fire engines, farmyard animals, puzzles, snakes and ladders, etc. For us girls, hand knitted jumpers, socks, a cot with sheets, pillows, pillowcases, beautifully embroidered blankets. Some received a magic chest, no key, you had to move certain parts to get the chest to open. There were dolls with a full wardrobe and cots for the dolls. I found out years later that Mum paid a small fortune to merchant seamen, dockers and stevedores for these things. She had been drafted into the Dockyard at Portsmouth, trained up as a master welder, so that through her job, repairing the merchant and naval ships, she had contact with the crews. We had the toys to play with for two days, then they disappeared, never to be seen again.

Prior to Christmas we had all to troop down to the kitchen and stir the pudding, which was very exciting. We tried very hard to get a smidgen on our finger so that we could have a sneaky taste. Peter remembers us going into the grounds to collect nuts for Christmas.

[My brother] Peter remembers one of the boys having a real problem with bed wetting and he was always being punished, usually no supper. The time was getting close to Christmas and he had been told that if he wet his bed he would have no Christmas. So, some of the lads took it in turns, Peter included, to hold him on the toilet while he slept. About an hour before wakey, wakey, they took him to bed so that they could snatch some sleep. Unfortunately in that hour he wet his bed, so he had no Christmas and was not allowed to join us for dinner or any of the other activities.

Echoes Of Home And Mum

Our silver-haired Naval Officer came to visit us twice while we were still at Luffness. In front of Matron he would ask us if we were happy, did we get enough to eat, were we well looked after. We gave the correct answers, would not have dared to do otherwise. He would then take us out for the day. Once to a big pond surrounded by brickwork where you sailed small boats across or waded in to rescue them by tucking your skirt into your knickers while boys rolled up their trouser legs. The second time he took us to see ‘Snow White’. Oh, what a joy that was but very scary too, especially the wicked Queen. Again he spoke very little but nothing was too much trouble for him. He also collected us, late 1944, early 1945, to return us to Portsmouth, same procedure as before, a carriage to ourselves.

In the grounds of Luffness were two cottages where a parent or parents could stay to visit you. The children moved down to the cottages to be with them. I remember Mum coming to see us, oh, the excitement knowing she would be with us soon. The anticlimax: we were strangers. We had changed and so had Mum and the week was almost gone before we found each other again. Then the heartbreak of parting once more. I recall I finally learnt to use a skipping rope properly for the first time. I had to have them all out to show off, forwards, backwards, bumps and crossovers. Oh, what excitement. Mum made some small cakes for tea as a treat. On the left-hand side of the cottage was a marker saying Rob Roy had stayed there, though my brother says it was Robin Hood’s name on the marker. There was also a long tunnel that led from the castle that came out by the cottages.

We both remember a white cow called Snowball we used to make a fuss of.

Punishment And Sex

On occasions we were punished by being caned. The same person always carried out the sentence. He was some sort of caretaker. There was abuse by some of the older boys on the younger boys. Whether this went all the way to sodomy or whether it was getting them to work them off, I do not know. The girls were also molested by the older boys, especially the well developed girls. They would try and push you up against a wall, try and pull your skirt up with one hand while they tried to grope your breasts with the other. They would also try and grind against you when they had a hard on.

If, while going back and forth to school, or on any other occasion, we saw Mrs Hope, the girls had to curtsy and the boys raise their caps. We believed she was a ‘lady’. It was some years before I found out that she not, just a ‘Mrs’ like my Mum.

I understand that in 1963, nineteen rooms were demolished. These had been the rooms we’d slept in. [Later, much later, I returned] and I saw changes in Luffness; not many. I also went to see a Mr Birse, who was a gardener in Luffness, but not until after the war. He has no knowledge of evacuees but does remember Polish wounded being hospitalised at Luffness after the war.

We were not happy or unhappy at Luffness. Our sane little world had been turned upside down, so we lived from day to day, hoping things would get better, not worse. We wrote our weekly letter home on a Sunday, looked forward to a letter back from Mum and longed for the day we could go home. You tried to put a shield around you so no one could hurt you and sometimes it worked.”

Doreen returned to Luffness many years later after her elder sister, Margaret had died. Doreen was given permission to spread some of Margaret's ashes over part of the garden of Luffness Castle.

For a further eye-witness account:

See BBC WW2 Peoples’ War - the reminiscences of Archie Bell, who was evacuated from Edinburgh to Dirleton and later to North Berwick and Aberdeen. His is reminiscence no A2073700 can be found HERE.

[Note:WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC.]

For a further eye-witness account:

See BBC WW2 Peoples’ War - the reminiscences of Archie Bell, who was evacuated from Edinburgh to Dirleton and later to North Berwick and Aberdeen. His is reminiscence no A2073700 can be found HERE.

[Note:WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC.]

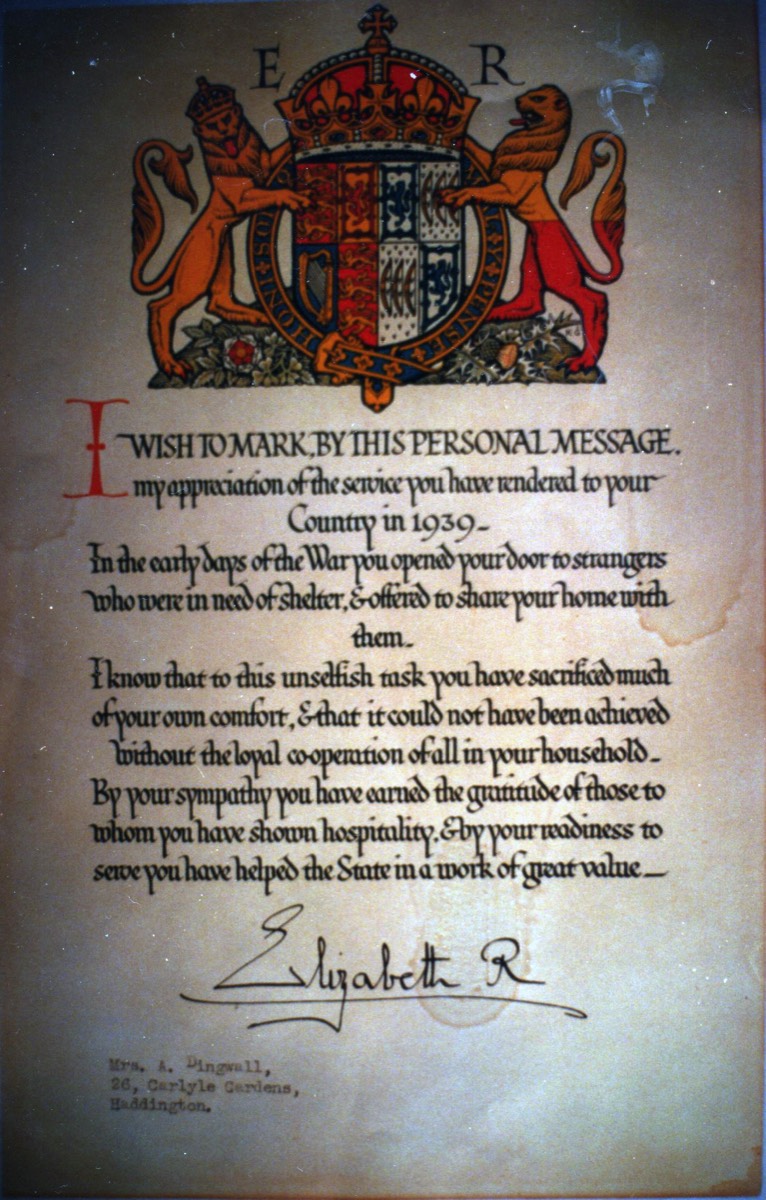

A certificate presented to Mrs A. Dingwall for her part in looking after evacuees during the war.